Free or heavily discounted public transport can help achieve social goals. But governments must carefully navigate equity considerations.

As part of a six-month trial, public transport fares in Queensland will soon be slashed to just 50 cents per trip for everyone.

The cheap fares will apply to all trips on buses, light rail, trains, and ferries, over any distance, in cities and towns that are part of the Translink network.

Very-low flat fares have become fashionable policy as governments respond to cost of living pressures around the world.

In 2022, Germany experimented with a flat-rate €9 per-month rail pass over a 90-day period. And just last year, the UK government implemented a £2 fare cap on many single bus journeys in England.

Last summer, Western Australia offered free public transport to SmartRider pass users for five weeks.

“Captive” users of public transport – who have limited access to private vehicles and few alternatives – would surely welcome such schemes.

But who stands to benefit the most? Is offering free or nearly-free public transport a good policy idea?

The benefits aren’t spread evenly

Some trips across Queensland will now be extraordinarily cheap. You’ll be able to travel from the Sunshine Coast to the Gold Coast for just 50 cents, if you don’t mind a four-hour trip on trams, trains and buses.

At an individual level, adults travelling the longest distances will benefit most. But as a group, commuters in the inner and middle suburbs of Brisbane and tertiary students will enjoy most of the benefits.

There are a few regional cities with well-frequented bus services, notably

Townsville and Toowoomba. Passengers travelling from Yeppoon to Rockhampton, or from Proserpine airport to Airlie Beach, will get inter-city travel at an amazing price.

But the regions will otherwise benefit less than in South East Queensland, given the limited demand for public transport, and the lesser provision of services.

Will people ditch their cars and get back on public transport?

Queensland’s government hopes the move will boost public transport usage and reduce congestion.

The impacts of low flat fares on patronage have been studied elsewhere. Early reports from Germany suggested that €9-a-month fares were popular and even led to some overcrowding during peak tourist seasons.

To investigate the trial, researchers conducted a before-and-after survey to understand behaviour changes. They found that public transport use did increase, but not all trips taken privately were substituted.

It has been argued that car ownership produces lock-in effects. Affordable fares are only one of the motivators that can encourage a shift to public transport. Buses and trains also need to be frequent, reliable and comfortable when competing against private car travel.

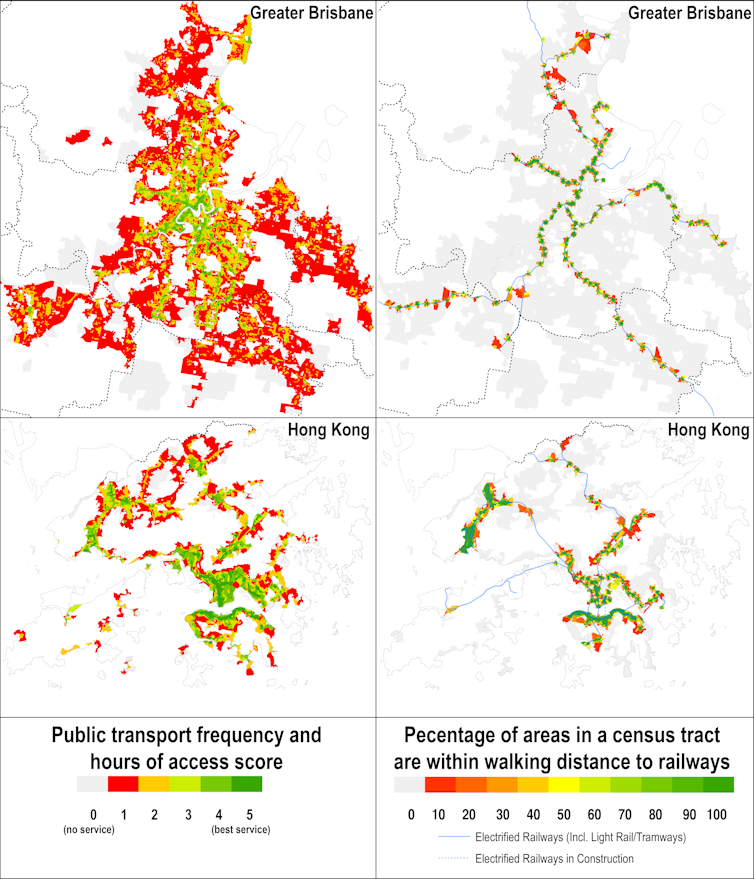

The layout of Queensland’s cities and towns is highly car dependent. Our previous work has examined how spatial layout and the availability of public transport affect its patronage in different cities. Transport statistics reveal only about 10% of trips use public transport in Brisbane, while the figure is as high as 90% in Hong Kong.

The new low fares might help relieve congestion on a few arterial roads where public transport corridors run alongside an alternative, most notably on the M1 motorway between the Gold Coast and Brisbane. But with limited public transport coverage across much of Queensland, heavily discounted fares may not lead to a dramatic uptake in use.

What will the social and economic impact be?

This leads to a bigger debate on how we should price public transport and who should pay for it.

There is no straightforward answer to this. Even when public transport is made very cheap or even free, someone ultimately has to pay for it. The merits of any pricing policy should be evaluated in terms of the winners and losers across society as a whole, referred to as transport equity. Equity can have two dimensions:

- horizontal – reducing inequality between people in similar groups

- vertical – giving a greater share of resources to disadvantaged groups.

Everyone in Queensland will now pay 50 cents, no matter how far they go, which creates strong horizontal equity between travellers.

But the wealthy have reclaimed the centre of Australian cities, including Brisbane. As these nearly-free flat fares benefit so many inner-city and middle-suburban commuters, a very hefty subsidy will be going to a group who don’t necessarily need it, paid for by other forms of taxation.

Are there other ways to subsidise public transport?

Yes. One alternative is to directly target programs to those in need, such as by ring fencing benefits to a smaller area. This was recently tested in Los Angeles under a program called Universal Basic Mobility.

A transport stipend of US$150 per month was provided via a debit card called a “mobility wallet” to residents of a disadvantaged neighbourhood. The card could be also used for e-scooters, taxis and even Uber or Lyft. Service improvements were also rolled out.

Queensland itself has long provided free fares where they are seen to have a social benefit. The largest city councils often provide free bus travel for seniors outside peak hours, and popular “free” public transport to large stadiums for concerts or sporting events is covered by a fee hidden in the ticket price.

The state has also trialled another alternative – the ODIN Pass – which provides affordable multi-mode (bus, train, ferry and e-scooter) trips for students via a “Mobility as a Service (MaaS)” smartphone app.

Free or heavily discounted public transport can be a good idea – where it can help meet social goals. But it’s best when targeted at the most disadvantaged.![]()

This article is authored by Abraham Leung, Senior Research Fellow, Cities Research Institute, Griffith University and Matthew Burke, Professor, Cities Research Institute, Griffith University. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.