China has spent 10 times more on clean energy than either the US or Europe over the past five years.

China is winning the clean energy race.

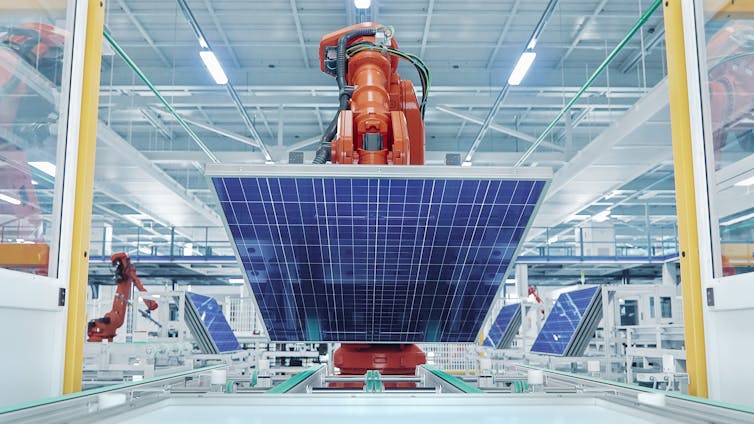

It has spent ten times more on clean energy than either the US or Europe over the past five years. It dominates the rapidly growing renewables manufacturing market, producing 90% of all solar panels, over 70% of all lithium batteries, and 65% of all wind turbines.

That’s a very smart move. Our recent research shows there’s no evidence that solar and wind cannot continue their recent spectacular growth rates. Renewables could become a multi-trillion-dollar global industry in the near future.

The eye-watering investments of the European Green Deal and the US’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – each close to US$1 trillion (£0.75 trillion) over the next decade – might close the gap in terms of their clean energy deployment, but they are unlikely to shake China’s market dominance.

China already processes most of the clean energy supply materials and has an advanced manufacturing base that is more capable of scaling up production to meet the rising demand. China’s Tongwei solar manufacturing plant, for example, could single-handedly meet 10% of the 2023 global solar market demand.

And some of the newer Chinese plants are designed to be modular. If demand continues to grow, another one or two such factories can be built relatively quickly – taking economies of scale to another level and bringing down costs even further.

To understand what is driving this spectacular growth in China at a city level, we canvased expert opinions from regulators, academics, industry and green groups in two leading Chinese cities: Beijing and Hong Kong. As one respondent in our survey summarised, in both cities the choice of decarbonisation policies is influenced by factors including “alignment with the national agenda, economic costs, ease of implementation, and the availability of co-benefits”.

One driving force is China’s pledge at the 75th UN General Assembly to achieve carbon neutrality or net zero emissions by 2060 – a state in which any carbon emissions are matched by the equivalent amount of carbon being pulled out of the atmosphere. This directive from the top is propelling cities towards their individual carbon neutrality targets, including Hong Kong’s target to reach carbon neutrality by 2050.

Renewables appear to be in favour in China at all levels of government. Leveraging the global cost declines in renewable energy and accelerating the electrification of transport were considered high-priority strategies at a city level. In contrast, for Beijing and Hong Kong at least, alternatives like capturing carbon from fossil fuel usage and storing it underground were seen as decisions for state officials, and only necessary for the “last 8% to 10% of hard-to-abate emissions”.

The net zero strategies of China, the UK, US and Europe all include renewables alongside extensive investments in alternative clean technologies, such as carbon capture on fossil fuel plants and nuclear power. The US has cheap gas – lots of it – and is building many multi-billion dollar facilities to produce hydrogen from renewables and carbon capture. Both the US and Europe also have a reasonably long history with nuclear.

China is investing in these alternative technologies, but not nearly with the same vigour as renewables.

Building on our previous research, we found that renewables and electrification of transport are increasingly attractive investments for city decision-makers in China because they are low cost, relatively low risk, and have the potential for generating persistent emission reductions at speed. These are qualities that make them rapid agents of change.

Runaway decarbonisation

Just as the climate system has tipping points that can result in runaway climate change, our socio-economic systems have sensitive intervention points (Sips) that can unlock runaway decarbonisation. Sips enable a moderate policy intervention to generate transformational change and outsized results via “kicks” (actions that trigger a positive feedback dynamic, such as learning-by-doing with renewables) and “shifts” (fundamentally altering the system to generate dramatic change, such as the UK Climate Change Act).

Our past research on Sips showed that renewables and electrification of transport rate highly as “kick” Sips because they have high learning rates: the more we produce, the more we learn, the more costs come down, and the more we demand.

There is an inexplicable magic to why some technologies have such high learning rates and others don’t. These learning rates, once established, turn out to be persistent and quite predictable. It is our belief that modularity, mass production and mass appeal are all important factors for high learning rates.

Solar, wind and batteries have all of these ingredients – but particularly solar. You can put a single cell on your wristwatch, build a large solar farm, and everything in between. Their technological progress lies in manufacturing and mass production, after which it is virtually plug-and-play to deploy them. And most people have a more positive attitude towards solar and wind than alternatives like carbon capture and storage or nuclear.

Lessons from two cities

What could countries like the UK, that don’t have China’s manufacturing base, do to stay in this clean energy race? Our colleagues at the University of Oxford’s climate econometrics research group have shown how five policy interventions could help bring the UK back on track with its climate pledges.

These proposals involve triggering both kicks and shifts to drive massive expansion of renewables – such as using electric vehicles as a network of storage units, and establishing more vertical and underground farms in inner cities.

The world now has less than 26 years to reach net zero by 2050. As urbanisation rapidly scales up and more cities unveil their net zero plans, we believe the most effective green transition policies will make use of “Sips-thinking” to accelerate progress.

This article was authored by Matthew Carl Ives, Senior Researcher in Economics, University of Oxford and Natalie Sum Yue Chung, PhD Candidate, Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment, Princeton University. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.