Dr Robin Lovelace and Dr Joey Talbot from the University of Leeds explain how transport authorities must act quickly to take advantage of the current cycling boom.

Cities worldwide are preparing for the long transition out of lockdown. Physical distancing measures will be in place for many months, with impacts on all walks of life, not least transport.

With public transport options running at low capacity and emerging evidence of the role of air quality and exercise in mitigating the risks of Covid-19, solutions are needed more than ever.

New cycleways are being introduced in many cities, allowing healthy habits started during the lockdown to continue. Transport authorities must act fast, however, to take advantage of the current cycling boom while traffic levels are still below normal, and to avoid gridlock.

Our research at the University of Leeds has identified roads where there is both space and demand for cycling infrastructure.

Our methods have been used in a nationwide project funded by the Department for Transport and transport charity Sustrans to help relieve immediate pressures on the transport system and create long term change. The result is the Rapid Cycleway Prioritisation Tool. This is a free and open tool to help ensure that the government’s Emergency Active Travel Fund is spent where it is most needed, for maximum long term benefit.

New routes

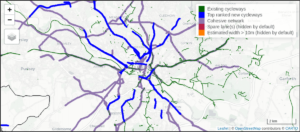

The Rapid Cycleway Prioritisation Tool provides an interactive map for every transport authority in England. The main result is a list of road sections that have both high demand and sufficient space for cycling.

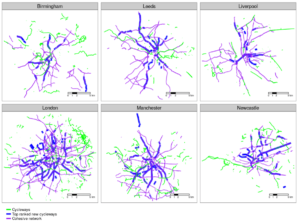

These are represented as blue lines in the map of Leeds below, many of which are included in the council’s new cycleway plans. Additional layers in the map include existing off-road cycleways (shown in green), which in many cities are disjointed or of variable quality, and, in purple, a vision of what a joined-up cycle network could look like.

This new tool builds on our previous work, carried out with other universities, to help authorities identify and develop strategic cycle networks. We created a national dataset of roads, including estimates of the number of lanes in either direction and road width.

This can help identify where roads have space that could be reallocated to widen pavements or to rapidly introduce new cycleways. One of the first of these has been installed outside a hospital in Leicester. Community engagement through projects such as Widen My Path, which provides a forum for comments on where more space for walking and cycling is most needed, is another vital part of this process.

The tool’s focus on road space reallocation is due to the importance of speed and capacity. Light segregation measures such as plastic bollards or wands can be implemented much faster than constructing new cycleways from scratch. Wide, direct and continuous cycleways, of the type created by road space reallocation on wide roads, are needed for capacity and to ensure physical distancing guidelines can be followed. Finally, road space reallocation has environmental benefits, representing “zero carbon infrastructure”.

An important finding is that many cities have wide roads with spare space, as shown on the maps of six major cities below. Notably, none of these yet have a joined-up cycle network. An example of the type of road highlighted by our tool is Kirkstall Road in Leeds, which has high cycling potential and sufficient width for new cycleways. Kirkstall road is already part of plans by Leeds City Council to become a trial cycleway.

Our methods, based on open data and code, could be used in cities worldwide. Given the global nature of the challenges we face, open and collaborative research is vital. The potential for international application can be seen in research we carried out for the World Health Organization on possible cycling uptake in cities in low income countries.

Planning for the future

The UK government has announced £2bn of investment in measures to promote walking and cycling in England over the next five years. £250m has been allocated for emergency interventions to make cycling and walking safer.

Similar commitments are being made in Scotland and Wales. Local authorities urgently need to decide how this funding should be spent.

If action is prioritised in places where there is a long-term need for cycle improvements, there is a greater chance that these developments can become permanent. In Paris, Covid-19 related measures aim to contribute towards mayor Anne Hidalgo’s long-term Plan Vélo.

New cycling infrastructure is more likely to be effective when it is developed based on analysis of the best available data, in combination with vital local knowledge. City planners, politicians and citizens need to act to ensure that transport interventions made during the crisis are of maximum benefit now and in the post-pandemic world.![]()

This article was authored by Robin Lovelace, associate professor in Transport Data Science, University of Leeds and Joey Talbot, research fellow in Transport Data Science, University of Leeds.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.