Reduced government incentives, the spreading of myths and concerns about used car values and fires have stalled what had been an increasingly rapid uptake of electric vehicles.

Battery electric vehicle sales in Australia have flattened in recent months. The latest data reveal a sharp 27.2% year-on-year decline (overall new vehicle sales were down 9.7%) in September. Tesla Model Y and Model 3 cars had an even steeper drop of nearly 50%.

Sales also fell in August (by 18.5%) and July (1.5%). There’s a clear downward trend.

Before this downturn, electric vehicle sales had been rising steadily, supported by increased choices and government incentives. In early 2024, year-to-date sales continued to grow compared to the same period in 2023. Then, in April, electric vehicle sales fell for the first time in more than two years.

Australia isn’t simply mirroring a broader global trend. It’s true sales have slowed in parts of Europe and the United States — often due to reduced incentives. But strong sales growth continues in other regions, such as China and India.

A range of factors or combinations of them could help explain the trend in Australia. These include governments axing incentives, concerns about safety and depreciation, and misinformation.

Governments are cutting incentives

Electric vehicles typically cost more upfront. However, the flood of cheaper Chinese vehicles is lowering the cost barrier.

Federal, state and territory governments also provide financial incentives to buy electric vehicles. These have been among the main drivers of sales in Australia.

Nationally, incentives include a higher luxury car tax threshold and exemptions from fringe benefits tax and customs duty. But several states and territories have scaled back their rebate programs and tax exemptions in 2023 and 2024.

New South Wales and South Australia ended their $3,000 rebates on January 1 this year. At the same time, NSW ended a stamp duty refund for new and used zero-emission vehicles up to a value of $78,000. Both incentives had been offered since 2021.

Victoria ended its $3,000 rebate, also launched in 2021, in mid-2023.

In the ACT, the incentive of two years’ free registration closed on June 30 2024.

Queensland’s $6,000 electric vehicle rebate ended in September.

The market clearly responded to these changes. However, reduced financial incentives alone cannot explain the full picture. Despite several rounds of price cuts, sales of popular Tesla models are falling.

Buyers are increasingly opting for hybrid vehicles instead. In September, sales of hybrid and plug-in hybrid vehicles were up by 34.4% and 89.9%, respectively.

These sales trends reflect other consumer concerns beyond just the upfront cost.

Resale value worries buyers

One major issue for car buyers in Australia, and globally, is uncertainty about their resale value. Consumers are concerned electric vehicles depreciate faster than traditional cars.

These concerns are particularly tied to battery degradation, which affects a car’s range and performance over time. And batteries account for much of the vehicle’s total cost. Potential buyers worry about the long-term value of a used electric vehicle with an ageing battery.

For example, a 2021 Tesla Model 3 Standard Range Plus with nearly 85,000km currently lists for about $34,000. It has lost roughly half its value in just three years.

While Tesla offers transferable four-year warranties and software updates, the rapid evolution of EV technology also makes older second-hand models less desirable, further reducing their value.

Fires raise fears about safety

Electric vehicle fires have made headlines globally. This has created doubts among consumers about the risks of owning them.

In Korea, a high-profile battery fire in August 2024 led to a ban on certain electric vehicles from underground car parks. While similar bans are not common in Australia, some have been reported. These could have harmed local consumer confidence.

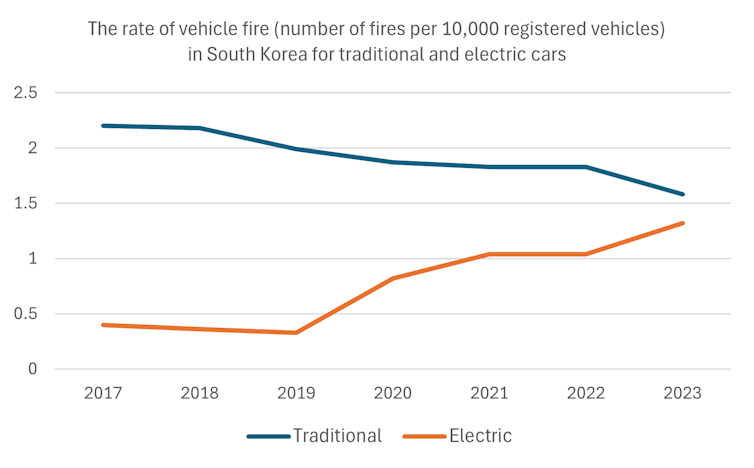

Incidents of electric vehicle fires have increased along with vehicle numbers. Statistically, these vehicles are not more prone to fires than conventional cars – in fact, the risk is clearly lower.

For example, analysis of publicly available statistics from South Korean government agencies, one of the early adopters of electric vehicles, show the number of fires per registered electric vehicle is steadily increasing. Fire risk remains lower than for traditional vehicles, although the gap is shrinking as the electric vehicle fleet ages. And the highly publicised nature of their fires is a source of growing buyer hesitancy.

Misinformation and politicisation are rampant

The full environmental benefits of electric vehicles depend on widespread adoption. However, there is a wide gap between early adopters’ experiences and potential buyers’ perceptions.

Persistent misconceptions include exaggerated concerns about battery life, charging infrastructure and safety. Myths and misinformation often fuel these concerns. Traditional vehicle and oil companies actively spread misinformation in campaigns much like those used against other green energy initiatives.

In response, coalitions such as Electric Vehicles UK have formed to combat these false narratives and promote accurate information.

The politicisation of green initiatives adds to the challenge. When electric vehicles become associated with a specific political ideology, it can alienate large parts of the population. Adoption then becomes slower and more divisive.

Green transition is a work in progress

The electric vehicle market in Australia is facing challenges, despite the growing variety of models and price cuts.

The EV sales trend signals deeper issues in the market. Broader trends, such as the dominance of SUVs and utes, underscore the fact that while the transition to greener vehicles is progressing, it remains uneven.

Further efforts will be needed to reduce misconceptions and misinformation, and bridge the gap between owners’ experience and potential buyers’ perceptions. Only then can Australia enjoy the environmental benefits of widespread EV adoption.![]()

This article was authored by Milad Haghani, Senior Lecturer of Urban Analytics & Resilience, UNSW Sydney and Hadi Ghaderi, Professor in Supply Chain and Freight Innovation, Swinburne University of Technology. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.