Gravelly Hill Interchange was always meant to be functional, but its cultural life has been rich too…

For half a century, Gravelly Hill Interchange – affectionately known as Spaghetti Junction – has divided opinion. Opening to much acclaim on 24 May 1972, it was the final piece in a major infrastructure project designed to connect several major routes (the M1, M5 and M6) at the heart of England’s new motorway system.

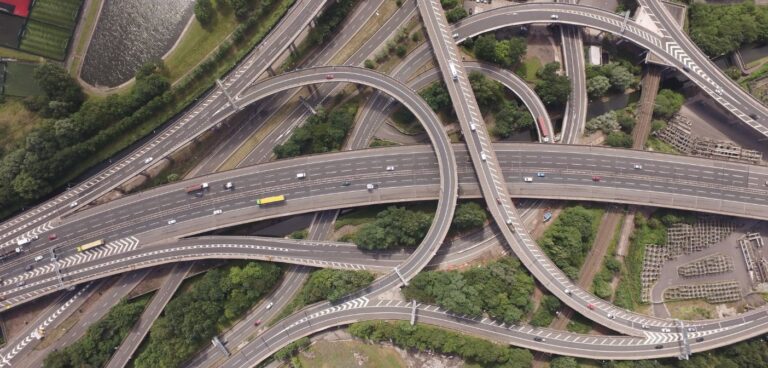

Significantly, the complex, layered concrete and steel structure – whose principal engineer was the London-born architect Evan Owen Williams – brought together national and local highways, ushering traffic into the city of Birmingham via the multi-lane Aston Expressway. It has always been more than just a traffic junction, though.

An engineering marvel, it came at some cost to local communities and the environment. To make way for its 12,655 tons of structural steel and 175,000 tons of concrete, 146 houses were demolished.

The landscape beneath was re-engineered, with the River Tame redirected and Salford Reservoir and park created. Beyond the river, the interchange spanned both the Grand Union and the Birmingham and Fazeley canals, the Birmingham and South Western railway line, and a major regional gas main.

This saw it heralded as a wonder of the modern world – unlike any other, even the road infrastructure Los Angeles was famous for. Writing in New Society in 1972, architectural critic Reyner Banham celebrated the “close-packed curving and intersecting perspectives of double files of columns, which seem the more extraordinary from the constantly changing viewpoint of a moving car”.

This offered, he said, a “tourist route” which took in the dynamic landscape of mobility. Gravelly Hill Interchange, to Banham’s mind, was “a big Brummagem artwork”. It has been central to the city’s cultural landscape ever since, featuring in my recently published Modernist Map of Birmingham at number 39.

How Spaghetti Junction changed Birmingham

Spaghetti Junction was a coup for Birmingham authorities, renewing the city’s place on the national and global stage. In the aftermath of the second world war, during which Birmingham was extensively bombed, the automotive industry was thriving. With greater affluence came greater mobility. As towns and districts to the north of Birmingham attracted suburban dwellers, commuter traffic increased.

For the bemused driver, the Birmingham Mail produced a three-part “cut-out-and-keep” guide, advising them to “use your eyes, drive on the signs, and you will untangle Spaghetti without trouble”. British motoring association the AA, meanwhile, attempted to allay people’s anxiety about using the junction. It advised its members that “a digital computer will analyse information collected by electronic detectors in the carriageway” to monitor accidents or breakdowns and prevent blockage.

The interchange changed more than simply the way people used roads, though, it changed the very understanding of the city, ushering in the modern era. Filmmakers were quick to capitalise.

In his pseudo-psychedelic 1973 musical Take Me High, British director David Askey follows the soul-searching exploits of merchant banker Tim Matthews (played by Cliff Richard) on his mission to save the Brumburger restaurant. In a statement on the transitionary state of the mid-century British city, Matthews chooses the canal as his home and mode of transit over the elevated highway of Spaghetti Junction – the latter used as a symbol of modernity.

In 1990, the Late Show asked five architects to speculatively reimagine the interchange as “free space” without constraints of planning or brief. One imagined interconnecting neo-classical towers as gateways to the city. Another proposed pedestrian pathways with picturesque belvederes and suggested replacing the housing nearest to the junction with a hotel as “a more appropriate building type for the site”. Spaghetti Junction was as much a destination as a transport nexus.

The canal towpath and service tunnels beneath the interchange have inspired artists too, including one who installed a a hair salon, including sinks, mirrors and upholstered seats. The site has also been home to large-scale photographic paste-ups of a verdant garden. Scottish artist and member of the band the KLF Bill Drummond even began and ended a a 12-year world tour at Spaghetti Junction.

Gravelly Hill Interchange represents the multiple identities and imaginations of the city. It is a world-beating wonder, an assemblage of sculptural forms, a fantastical filmset-like location. It was a local triumph at its birth, received with municipal fanfare. And despite its functional role, it has been a free space ever since, enabling open dialogue on the state of contemporary society. With the changes brought about by new fuel and communication technologies, perhaps a cultural calling is in its future too.![]()

This article is authored by Michael Dring, senior lecturer in architecture, Birmingham City University. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.