During Covid-19 European cities adopted a range of emergency transport policies. Could this framework of interventions go beyond the pandemic and create more inclusive and sustainable cities? Alessandro Balducci, Professor of Planning and Urban Policies, and Paola Pucci, Professor of Urban Planning of Politecnico di Milano, explore the application of such mobility policies, in particular the case of Milan…

Italy was the first Western country hit by the pandemic. Milan, the capital of Lombardy, the region worst hit by Covid-19, has worked on recovery policies that consider a transition period whose duration we do not know yet.

It is interesting to reflect on the measures implemented by the Municipality of Milan regarding mobility in the document Milano 2020. Adaptation strategy drafted during the lockdown, as to some extent they seem to be representative of a more general situation regarding mobility policies in major European cities.

Due to their characteristics, these measures may represent both a simple adaptation to a crisis or the opening of a new period in terms of city development, capable of moving toward the direction of the 11th objective of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, aimed at making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

Just a few weeks after the approval of the strategic plan for the city – Milano 2030 – which envisioned an image of a competitive, innovative city of operational excellence and a hub of international relations, the pandemic forced a rethinking of this narrative.

In the Milano 2020 document, therefore, the directions propose to orientate concrete actions and limit the effects of the pandemic on residents’ daily lives. The operation of economic and social activities offer a framework of necessary, quickly implementable interventions regarding the organisation of the transport system, the design of public spaces, and the distribution and operation of urban activities.

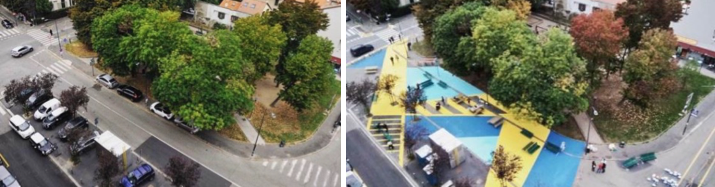

These are tactical actions that have and can be realised in the short-term through experimental interventions that act as planning ‘accelerators’, some of which are already present in ordinary tools implemented before the pandemic.

The measures tested for the crisis are based on interventions aimed at redesigning public spaces in favour of active mobility. They propose a change of scale in urban density inspired by the concept of ‘accessibility by proximity’ (the 15-minute city), supporting actions to de-synchronise urban times to avoid rush hours, and forms of smart working that contain necessary movement.

New bike lanes (35km currently in project) in place of parking plots, are changing the perception of public spaces, along with the reallocation of spaces from cars to pedestrians, through a tactical urbanism project known as ‘Strade aperte’. Measures to implement accessibility by proximity on a district scale create the conditions for a more inclusive city, supporting the redistribution of urban services at the neighbourhood scale.

These interventions, accelerated by the crisis, fall under policies to support decarbonisation (a post-carbon city) and a more equal distribution of services, reinforcing the image of the city as a lab for urban experimentation and innovation.

They use the fringes of experimentation and flexibility endorsed by the pandemic, putting pressure on the temporary nature of solutions necessary to face the post-Covid period. At the same time, however, they expand the framework of interventions that the city had already initiated with the creation of new underground lines (lines 4 and 5), private car restriction policies (i.e. congestion charge in ‘Zone C’, and more recently ‘Zone B’, which covers nearly the entire municipal territory), together with the incentive of providing sharing-mobility services.

However, there are still open issues, such as the paradox of incentive measures to encourage the private purchase of EVs in a city where instead e-sharing mobility and integration with public transport should be supported; a still-incomplete rate supplementation that underlines the difficulties of governance between Milan, municipalities in the metropolitan area, and transport agencies; and local public transport services that do not cover the demands of some jobs such as those with atypical time slots (night shifts).

Nevertheless, Milano 2020 and the actions promoted to address the post-Covid period related to the mobility sector, establish a framework of interventions that go beyond the crisis and may even draw on this strength to glimpse an idea of a more inclusive and sustainable city.