The EV transition is exposing social, economic and geographic disparities between communities across the country. Katie Searles discovers what’s being done to ensure no-one is left behind during the electric switch…

In October 2021, the UK government yet again placed the shift to electric vehicles (EVs) at the forefront of its net zero strategy. Following on from UK prime minister Boris Johnson’s 10-point plan to decarbonise the country, announced earlier in the summer, this latest strategy focuses on £620m investment for on-street residential charging and a £330m zero-emission vehicle mandate to support automotive manufacturers produce and sell a proportion of clean vehicles annually.

While the net zero strategy is part of the UK’s commitment to green energy ahead of COP26, it also mirrors current consumer demand for clean cars. September 2021 was the best month on record for new battery-electric vehicle (BEVs) uptake, according to figures published by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT). With a market share of 15.2%, some 32,721 BEVs joined the UK road network that month, reflecting the wide range of models now available. Indeed, the September performance was just over 5,000 shy of the total number of EVs registered during the whole of 2019.

Furthermore, the all-electric Tesla Model 3 was the best-selling new car overall during the same month. While these facts and figures show an increasing electric aspiration, when compared with other like-sized nations – such as Norway, which recorded electric car sales of nearly 80% in September – the UK still lags behind. Indeed, nearly half of all new car registrations in the UK remain vehicles powered by fossil fuels (43.8% petrol and 5% diesel). But what’s behind the lag? Is it the price of new EVs, range anxiety brought on by limitations with current battery technology or perhaps a lack of adequate public charging infrastructure that’s accessible to all?

Chicken and egg

According to charging station contractor Connected Kerb, inequality threatens to derail the country’s EV adoption drive. For example, the company cites SMMT data on car registrations in August 2021, which shows that UK EV registrations were already up 117% on all of 2020. However, it also points to research by home chargepoint manufacturer Anderson, which analysed Zap-Map data to rank the best and worst areas in the country for access to street chargers. It found that those living in urban centres, high-rise f lats and council estates are significantly less likely to have access to a private driveway, thus making it difficult to install home charging solutions.

As a result, households with access to a driveway reportedly make up 80% of all EV owners in the UK, with the remaining 20% owned by those in houses or f lats with no access to off-street parking. This, says Connected Kerb, is ironic given that these communities have the most to gain from clean transport due to being disproportionately exposed to the highest levels of toxic exhaust emissions and suffering significantly poorer air quality.

“Unfortunately, some communities are being failed by a classic chicken and egg scenario,” says Chris Pateman-Jones, CEO of Connected Kerb. “Without high EV adoption, chargepoint operators won’t build public charging, and without reliable charging, why would anyone go electric?”

This is why the company has partnered with Lambeth Council in London on a project designed to demonstrate how affordable and accessible public charging infrastructure can be deployed to tackle EV inequality and drive greater EV adoption amongst communities traditionally under-represented in the EV transition. Chris Pateman-Jones says the project, which is funded in part through the UK government’s On-Street Residential Charge Point Scheme, could act as a blueprint to be adopted at scale by other boroughs, councils and cities to deliver a fairer EV transition.

According to Lambeth Council, approximately a third of residents in the London borough live on estates managed by the council and the majority of housing does not have off-street parking, meaning a large proportion of drivers have to rely on public EV charging infrastructure. It aims to change this via 22 on-street EV chargers across 11 council estates that provide easy access to public charging, including those without off-street parking. Each Connected Kerb charger provides a 7kW fast charge, suitable for habitual on-street charging where residents are parked for a predictable amount of time each day. Every chargepoint also features contactless payment via the Connected Kerb app with a consistent network and tariff across the sites.

What’s more, the charging infrastructure is located below ground and installed once, with passive chargers that can be easily ‘switched on’ by adding the above ground charge point to match consumer demand. According to Connected Kerb, this business model means Lambeth has access to a secure revenue stream to help maintain and expand the charger network. The project forms part of the council’s wider strategy to work with multiple chargepoint operators to install more than 200 charge points by 2022, with the aim of ensuring every household with no access to off-street parking is within a five-minute walk of the nearest charge-point.”

For residents who need to use private vehicles, we recognise how important access to EV charging is to provide the confidence to switch to cars with zero emissions,” says councillor Danny Adilypour, cabinet member for sustainable transport, environment and clean air at Lambeth Council. “Projects like this help us do just that, while also helping us reach our net zero targets and improve air quality on our streets, protecting the health of our communities.”

Inclusion illusion?

But what good is a reliable, public EV charging infrastructure if it can’t be accessed by drivers with mobility issues or any of the country’s 2.44-million registered Blue Badge holders? Surprisingly, the UK’s first fully accessible electric charging point, specially designed for drivers with disabilities, wasn’t unveiled until January 2020 – representing just 0.003% of all charging locations across the country at that time.

Later that year, the Research Institute for Disabled Consumers (RiDC) undertook a study on behalf of disability charity Motability into EVs and charging infrastructure that highlighted a clear lack of consideration for disabled motorists as users or potential users of EVs.

“The speed and the scale of the rollout of EV infrastructure and electric cars has been very fast,” says Gordon McCullough, CEO of RiDC. “And with that, the views and insights of disabled and older drivers – while perhaps not being wilfully ignored – certainly have not been included in the planning or design of the charging infrastructure.”

During its research for Motability, the RiDC went with some of its members to a garage forecourt in Hammersmith to experience what it was like for someone with a disability to charge an EV. “One person said, ‘This feels like losing five years of the independence I have struggled to get through my car’,” McCullough recalls.

He praises the work that Motability has done and its foresight in commissioning research into EV accessibility. Along with fellow disability charity Designability, Motability has worked to engage with disabled people and identify what accessible charging truly looks like. The two charities have studied the physical aspects of charging – whether that be the built environment such as the parking space itself or the area around it. They have also looked at access in terms of the charging process itself, interaction with the charging unit, cables, payment instructions, signage, connectors and sockets.

Keir Haines, senior product designer at Designability, says: “It is clear from our research with disabled EV users that public charging solutions are failing them in many ways. There are many barriers that need to be removed and there are processes that need to be simplified, from payment processes and the interactive element of charging to cable management and even where the socket is on the car.”

Warren Philips, director of IT and communications at Electric Vehicle Association England (EVA), an organisation designed to accelerating the mass adoption of electric cars through provision of accessible information to consumers, and strategic campaigning to UK government on key policy matters, agrees that something needs to be done. With an anticipated 2.7 million disabled drivers in the UK by 2035 we need to get this right.”

Standard bearers

As a result of the efforts of the likes of the RiDC, Motability and Designability, the UK government is now working to develop accessibility standards for chargepoints across the country. Specifically, the Department for Transport (DfT) has commissioned the British Standards Institution to develop industry guidance on how to make individual chargepoints more accessible by summer 2022. These standards will include a new, clear definition of ‘fully accessible’, ‘partially accessible’ and ‘not accessible’ public EV chargepoints.

Both Designability and Motability are on the steering group. “It’s about getting something out there fairly quickly that the industry can use to develop solutions that are more accessible than what currently exists today. The success of that process is delivering something that puts EV chargepoint accessibility for all on the agenda,” says Haines. Philips is also confident that the standardisation will help and believes “a good framework to protect and enable all vulnerable members of society” can be established.

However, McCullough wants this information to be integrated into charging location maps, and even Google Maps, to help disabled EV drivers confidently plan their journeys. He describes the current method of locating chargepoints as the “wild west”, with multiple apps on the market. He also feels the same about payment. With over 40 chargepoint suppliers across England and Wales, and ChargePlace in Scotland, there are also a range of payment methods to contend with.

“The entire digital infrastructure around electric charging has been overlooked from a disabled person’s point of view,” says McCullough. “Payment is interesting because you’ve got multiple operators and different apps, and working through all that is a problem for all EV drivers. However, that problem magnifies and increases for someone who’s not technically able or for someone with dexterity issues.”

Thus, some believe that standardisation of payment options is also required. Emily Chissell, director of markets for the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), says, “We’re calling on the government to make sure charging is simple and quick to pay for, including contactless options and no sign-ups required. Only 9% of all chargepoints currently offer contactless and we think that must change.”

Could a collaborative approach help transform the unruliness of the current ‘wild west’ situation? Philips says he has seen roaming partnerships form in the marketplace that enable drivers to have one card that provides access to chargers from multiple providers. He also believes a more competitive pricing structure will help address the issue of inequality.

“Wealthier people tend to buy new cars but as more EVs filter into the second-hand market we will see prices become more affordable to the everyone,” says Phillips. “We have EV drivers from a wide variety of backgrounds and there are some reasonably cheap EVs out there if you can live with an early model with a lower range. And if you have the ability to charge at home it can be very cheap motoring as there is little maintenance, no vehicle tax and the running costs can be as low as 1p per mile in fuel.”

Post-code lottery

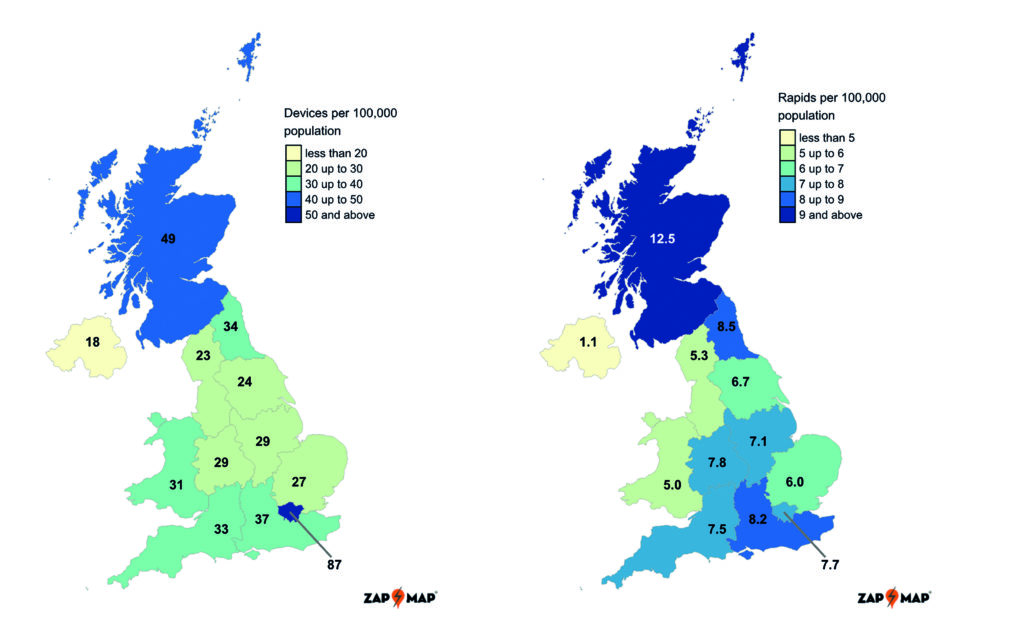

The ability to charge at home is, as established earlier, a contentious issue that intensifies when considering Deloitte’s prediction that, following the government’s ban on the sale of new fossil-fuel vehicles in 2030, some 43% of car owners will not have a driveway or access to private charging. It is therefore of no surprise that spacious Scotland currently leads the way in terms of numbers of chargers per resident, with 49 devices per 100,000 residents, compared to 39 devices per 100,000 in England, 31 in Wales and only 18 in Northern Ireland, according to the DfT’s latest EV charging device statistics. The report, released on 21 October 2021, conveys that “there is uneven geographical distribution of charging devices within the UK”.

Indeed, the apparent disparity of public chargepoint installations within England also suggests that the problem isn’t just national, but regional. For example, London has 87 public chargers per 100,000 people living in the capital – the most in the UK – whereas the North West, Yorkshire and the Humber have only 24 chargers per 100,000. “Latest figures put the number of on-street chargers at around 5,700, yet only 1,000 of these are outside of London – so there is a real risk of areas being left behind,” says Chissell. “Finding an electric chargepoint to power your car just isn’t as easy as it should be yet.”

The divide is also apparent in the funding figures. In August, the Office for Zero Emission Vehicles (OZEV) revealed the number of grants it had awarded for the installation of EV charging devices across the UK via the Electric Vehicle Homecharge Scheme (EVHS) up until 01 July 2021. Those in the South East benefitted most, accounting for 20% of total devices installed under the scheme. Meanwhile, Northern Ireland had the lowest number of EVHS-funded installations with 2,736 charging devices, this accounts for just 1.7%.

Regarding OZEV’s Workplace Charging Scheme (WCS), the South East once again had the highest uptake with 2,465 sockets installed while Wales and Northern Ireland had the lowest. Combined they accounted for just 5.9% of total sockets installed under the WCS in the UK.In total, OZEV has funded the installation of 1,459 public charging devices since the On-Street Residential Chargepoint Scheme was established in 2017, representing over £4.5m of grant funding across 49 councils. An additional 88 local authorities have also been awarded grant funding, providing 3,282 on-street public charging devices with their installations yet to be completed.

Haines said he hopes these local authorities will consider accessibility when using funding to plan where to place new chargepoints. “I’d like to see councils locate them in areas that give the most scope for maximum accessibility,” he says. “Instead of placing chargers at the edge of a small town, where there may be space but no nearby facilities, EV chargers should instead be installed near amenities and in locations that make people feel safe.”

Additionally, keeping track of where public chargepoints are installed could be just as vital to ensuring that those without access to an off-street charger are not left behind. “Data can help us make sure that chargers are installed in the correct places, helping people without off-street parking to still have an EV,” says Philips. “Knowing there are chargers available and working when you want to charge is essential to alleviating anxiety and having data available and made understandable is key to ensuring the smooth uptake of EVs in the run up to 2030.”

This article was originally published in the November 2021 issue of CiTTi. Click here to view the original article.