Bradford has recorded its lowest level of air pollution since records began, following the introduction of a clean air zone. Sally Jones, environment manager for City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council, reflects on the scheme’s successes and challenges…

When did Bradford introduce the clean air zone (CAZ) and why?

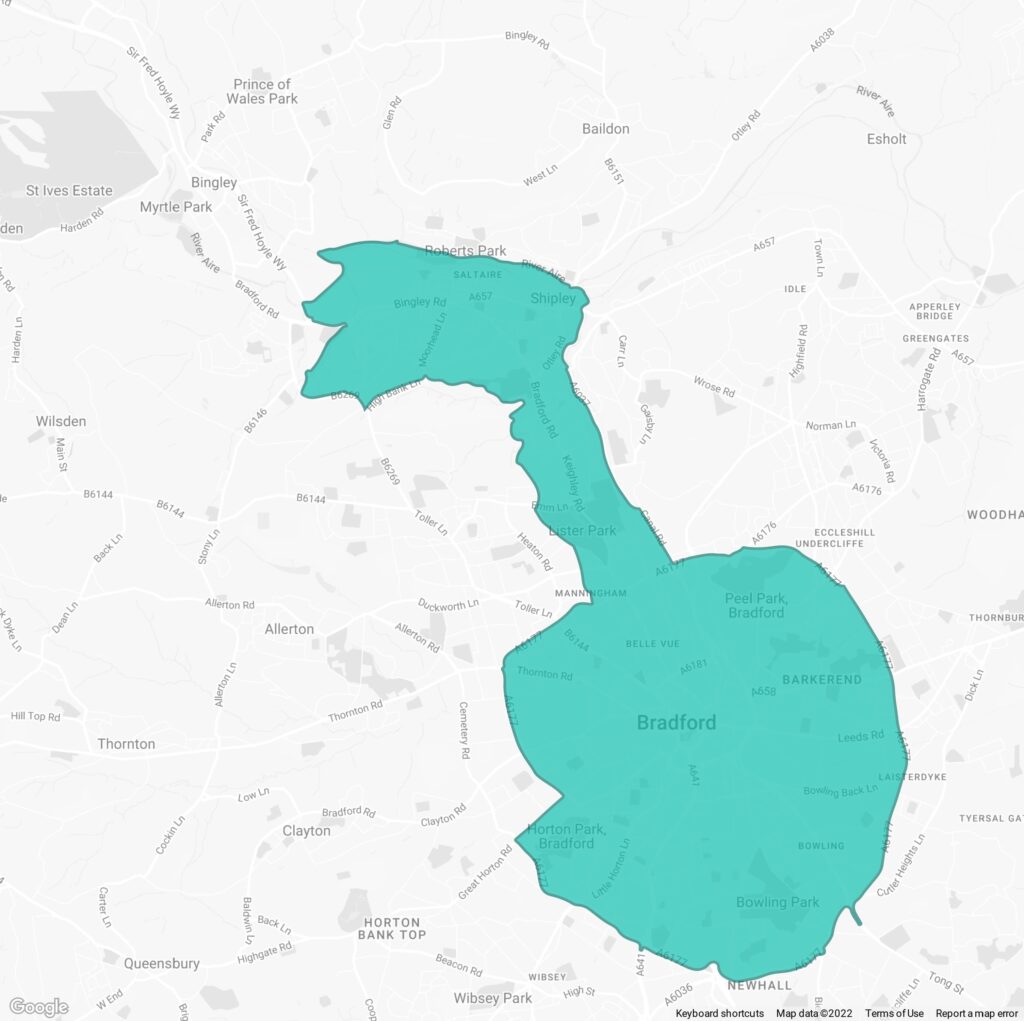

The CAZ was introduced on 26 September 2022 as air quality in Bradford had exceeded the legal limits for a long time. We’d been reporting that to the UK government since around the year 2000, but it wasn’t until around 2018 that the government said we had illegally high levels of air pollution in the city and that they wanted to start a discussion around what would be done to correct that. The government then brought out a CAZ framework and directed us to put in place a Class C+ CAZ, which includes buses, coaches, taxis, private hire vehicles, heavy goods vehicles, vans, minibuses. It doesn’t include private cars and motorbikes.

How did you decide that a Class C+ CAZ was the most appropriate type for Bradford?

We modelled all options and the government said we would probably need a Class C CAZ. However, when our own local data came back, our fleet was older than what the UK government had been modelling. This caused displacement with people trying to go around the zone on inadequate infrastructure, which affected our local fleet and a lot of deprived people. Deprivation has its own problems, and if you make it difficult for people to get to work, that can result in its own health impacts. The other option discussed was Class B CAZ, which would have charged heavy goods vehicles and not vans. Unfortunately, that option couldn’t get us to where we needed to be legally. It didn’t clean up air pollution enough. So, ours is a Class C+ CAZ – our taxis have got a slightly higher standard to reach that’s cleaner. Most of the taxi fleet and private hire vehicles are asked to be petrol hybrid, which is cleaner than Euro six (diesel).

What technologies or systems have been deployed in the CAZ?

It’s the biggest digital engineering project the council has ever undertaken. The Bradford CAZ was the first to launch in the north and we’ve got more than 330 automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) cameras installed across the zone. All the camera data we collect from the vehicle number plates goes to the DVLA, which collects the charges and tells us who we still need to pursue. We bought and installed the ANPR cameras ourselves, which is how we’ve kept the cost down. We also did all the system testing ourselves, which was cheaper than working with an external company, but what’s difficult for other cities is that timelines change and its challenging to get private companies to help you out.

Did Bradford consider alternative measures before implementing the CAZ?

Bradford set out lots of different options of how to meet the legal limit. For example, we wanted the government to fund a switch to electric buses, which would have made a massive difference. We also wanted a new train station, among other things that could have been done to improve air quality. But the government was really focused on putting in a charging CAZ to protect an area and keep out dirty or older vehicles. The science they applied and the modelling they’d done indicated that a CAZ was what cities such as Bradford needed. We had to work with the government and show them how much difference a CAZ would make using our own local data. But we knew the impact pollution was having on health. One in five children in Bradford have a respiratory problem and nearly 40% of asthma cases here are caused by traffic pollution. Our politicians knew this was having a bad effect on people in Bradford and that something had to be done.

What are the main impacts of the CAZ since its implementation?

Bradford’s air pollution is quite complex to measure. When everybody is in the city centre in the day and there’s peak congestion, pollution levels are way higher than they are in, for example, the middle of the night. Also, when it is cold, cold air sits on top of a city – it’s like a little pressure cooker – and all the pollution that’s been given off by vehicles, industry, people burning in the houses, gas boilers, all sits in the city. What we do is average the pollution level at a point in time over a year and then compare it with whether we’re meeting the legal limit or not. The pollutant we’re concerned about mostly is nitrogen dioxide because it’s a respiratory irritant that’s connected to heart conditions, strokes, asthma, and chest-related ailments. Bradford’s pollution level is gradually starting to come down to where it’s not illegally high anymore and, during the summer of 2023, we measured the lowest levels of pollution that we’d ever measured in the city.

How exactly is Bradford achieving a reduction in air pollution through the CAZ?

We have a massive support programme with loads of grants going out – more than £30m going out to companies. For example, every single taxi driver – taxis constitute 10% of inner-city vehicle movements in Bradford – was offered a grant and 99.5% of all licensed taxi drivers in Bradford are now driving compliant vehicles. When the fuel crisis hit, they were all saving money because they were driving around in petrol hybrids that don’t use as much fuel. Additionally, all buses in Bradford now meet the standard following the receipt of government funding for operators to purchase new, clean buses. Private companies are also receiving grants that enable them to upgrade their vans and lorries. We’ve halved the number of non-compliant vehicles entering Bradford city centre because of the standards of the CAZ.

CAZs divide public opinion – how did you navigate this when implementing the scheme?

I’m not saying we didn’t get pushbacks, because you’re never going to do something that makes everybody happy, but what we did do was get our support package right and listen to people. Not only have we received decent levels of support to help Bradford’s businesses upgrade their vehicles, but we also set up an exemption programme. For example, any resident in Bradford who lives in our district – and not just within the zone – with a commercial vehicle that doesn’t meet CAZ standards can apply for exemption from the scheme and enter and leave the zone without being charged. There’s still grants available to this day, such as £4,500 toward a new van that meets the standards. We tried to set the scheme up in such a way that residents of Bradford can live with it. Bradford is a through route – some 85% of the commercial traffic that passes through the city comes from outside of Bradford, only 15% of traffic is native to the district.

How many vehicles currently comply with the Bradford CAZ?

Nearly 97% of vehicles that enter the CAZ aren’t charged. Only 3.5% of the vehicles that pass through it aren’t compliant, which may not sound like a lot, but older commercial vehicles can be tens of times dirtier than the newer Euro 6 diesel vehicles, so the CAZ makes such a difference to the city’s air quality overall.

How much money has been raised by fines and where is the revenue directed?

The CAZ has generated approximately £10m since it launched in September 2022. As part of the Transport Act 2000 the government ringfences money raised through the CAZ and earmarks it for reinvestment into Bradford’s transport network. Half of our schools located are within the CAZ, so we’ve set up a clean air schools’ programme, which involves wardens dealing with anti-idling and traffic problems around schools. Schools can also apply for up to £10,000 to improve air quality via initiatives such as new footpaths to school bike shelters, bike schemes, walk-to-school schemes, and green barriers to protect playgrounds.

Does Bradford plan to retain the CAZ if it succeeds in bringing air pollution down to within legal limits?

We’ve done research in Bradford that shows that when our monitors are reading high, loads more people are turning up at A&E with respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses. The government’s joint air quality unit is tasked with the responsibility of making sure the UK meets its legal limits for air quality. After it linked Ella Kissi-Debrah [the first pollution-related death in the UK] to air pollution, we realised there are thousands of those kids in Bradford.

What advice would you give to other councils that want to implement a CAZ?

Communication is key. In Bradford, we’ve spent a long time working with partners, including the NHS, educating people on what the problem is and why we need to deal with it. You can’t impose something on people, they need to be able to understand it and know why you’re doing it. When we talk with taxi drivers in Bradford, their kids go to school in Bradford. They’re brought into the scheme knowing it’s to help their families and those around them. We held workshops with taxi drivers and found out they couldn’t afford to buy a new car then get the grant later, so we changed our system to account for that and it changed everything overnight.

This article was originally published in the February 2024 issue of CiTTi Magazine.

Achievements and innovations in sustainable urban mobility will be celebrated at the third annual CiTTi Awards, which will be held on 26 November 2024 at De Vere Grand Connaught Rooms in London. Nominations are now officially open! Please visit www.cittiawards.co.uk to learn more about this unmissable event for the UK’s transportation sector.