Once a cornerstone of Britain’s industrial revolution, inland waterway transport has dwindled. But amid the drive for greener logistics, could the UK’s canals and rivers be transformed into sustainable freight corridors?

In Birmingham’s public houses, it’s often claimed that the City of a Thousand Trades is more aptly named ‘The City of Canals’ – even surpassing Venice. Climate differences aside, both cities’ extensive canal networks (Birmingham’s once spanned 170 miles) were instrumental in transforming their nations into industrial powerhouses. At its peak during the UK’s canal ‘Golden Age’ (1770s-1830s), a 4,000-mile network transported millions of tonnes of goods.

Today, however, inland waterway transport in the UK is in decline, despite a brief revival in 2019. In contrast, European rivers such as the Elbe, Danube and Rhine are thriving. Consultancy firm IMAP values the European river freight market at £8.12bn, growing 5% annually. As an island nation reliant on international trade, the UK’s rivers and canals have untapped potential to serve as crucial logistics arteries once again. With inland waterway transportation at a crossroads, how are the organisations championing river freight navigating the challenges and opportunities ahead?

In 1997, following an 18-year hiatus, the newly elected Labour government set out its vision for British freight’s future. Its 1998 white paper, ‘A New Deal for Transport: Better for Everyone’, pledged to “encourage greater use of inland waterways, where that is a practical and economic option.” Yet, a 2023 government assessment revealed that domestic waterway freight – defined as ship freight transported along rivers or canals – had hit an all-time low, with only 15.4 million tonnes moved annually. Despite efforts by successive governments to tackle road congestion, why has inland waterway freight continued to decline?

Way of the water

Inland waterway transport can broadly be divided into two cargo types: liquid bulk and dry bulk. Liquid bulk, which involves transporting liquids such as fuel, has seen a significant decrease, attributed by the UK government’s ‘Port Freight Annual Statistics 2023’ to the decline of North Sea oil and the efficiency of road transport for liquid freight. Dry bulk, traditionally comprising raw materials, now also includes break bulk – smaller, individually packaged items such as household goods. During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, dry bulk imports surged, but these goods were offloaded at ports and transferred to heavy goods vehicles (HGVs), bypassing historic canal and narrowboat routes.

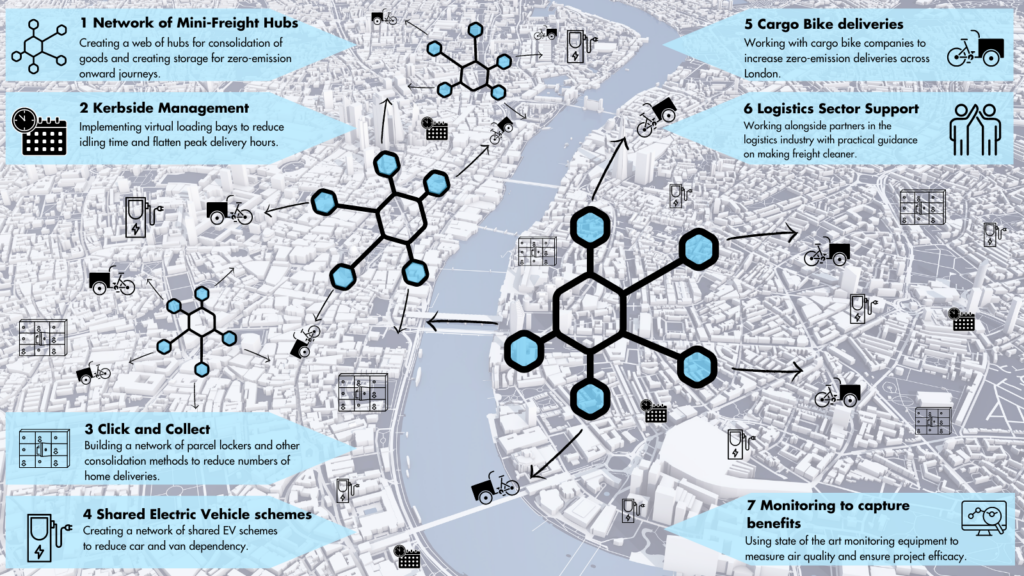

The Cross River Partnership (CRP), a non-profit organisation focused on revitalising London’s waterways, suggests that reorganising the delivery of the 450 million parcels distributed annually in the UK capital – 80% of which currently rely on road transport – could ease congestion and improve air quality by leveraging inland waterway transport.

“One of the biggest barriers is that the river has been viewed as a passenger transport opportunity rather than a freight solution. If we want to deliver goods at scale on the river, we need to rethink the design of our piers” – Fiona Coull, senior programme manager, Cross River Partnership

“One of the biggest barriers is that the river has traditionally been viewed as a passenger transport opportunity rather than a freight solution,” says Fiona Coull, senior programme manager at CRP. “If we want to deliver goods at scale on the river, we need to rethink the design of our piers. For example, an operation involving 12 tonnes of goods would require 10 cargo bikes just to offload items from a single pier. Infrastructure needs to accommodate segregated zones for passenger and freight traffic, shared usage areas, and pedestrianisation. This shift in perspective must be reflected in how we develop and adapt the river’s infrastructure.”

As the UK has shifted from a resource-based to a service-based economy, inland waterway transportation has evolved in parallel. According to the Inland Waterway Association (IWA) 2022 report ‘Waterways for Today’, an estimated 10 million people visit British waterways annually for recreational purposes, with leisure traffic now accounting for 58% of total waterway use.

“A recent report highlighted that Britain’s inland boating and tourism sector contributes £7.6bn annually to the UK economy,” says Amy-Alys Tillson, campaign officer at the IWA. “There are significant employment opportunities in sustainable freight tied to tourism and recreation. While waterways are often viewed primarily as leisure spaces, this perspective overlooks the many thriving businesses that they support and enable.”

Most restored locks, piers and waterways have been revitalised for tourism, often limiting their potential

for freight use. Increasing inland waterway transport freight requires overcoming challenges such as high costs, inadequate infrastructure, competing priorities, spatial constraints and competition from other transport modes. To address these issues and integrate the benefits of road and rail, advocates

are promoting multimodal transport hubs that incorporate inland waterway transport alongside

other transport methods.

FAST FACT: Inland waterway freight produces up to 75% fewer CO2 emissions per tonne-kilometre than road freight. Source: Logistics UK

“For our Waterloo urban logistics hub, we are exploring a space underneath Waterloo Station, where the old Eurostar used to deliver,” explains Coull. “It’s a vast area with access to rail, river and road, which could facilitate the use of cargo bikes and electric vehicles.”

“Loss of wharfs to development is a major barrier to inland waterway freight,” adds Tillson. “To succeed, transmodal hubs that connect waterways with other transport modes are essential.”

As cities grow denser and roads become increasingly congested, previously overlooked spaces are gaining new importance. The piers lining the UK’s rivers and canals are no exception. Unused sites that have yet to be refurbished can be repurposed and, where possible, integrated with existing transport hubs. Expanding reliance on inland waterway transport and modernising infrastructure are vital to its regeneration and boosting freight volumes.

“That’s another thing we’re exploring to support the narrative of more freight into central London,” says Coull. “What business areas could you serve by utilising this pier? Are there opportunities for urban consolidation, such as repurposing disused car parks for consolidation sites or replenishment services in areas difficult to access by vehicle?”

Land-based vehicles, such as cargo bikes or HGVs, could further enhance sustainability by adopting renewable fuels. For inland water transport, which requires higher-density fuel sources, biofuels are emerging as a viable option. “We’re also working to promote the use of hydrotreated vegetable oil [HVO] to improve the sector’s sustainability,” says Tillson. “HVO makes boating more sustainable by replacing fossil diesel with a second-generation biofuel.”

Go with the flow

Inland waterway transport is unique among British freight options, as much of its historical infrastructure still exists. Roads that once carried horse-drawn carriages have been paved for cars, and railways have evolved to accommodate high-speed electric and diesel locomotives. By contrast, the rivers and canals that once supported inland water transport remain largely unchanged, aside from some canals severed from their major tributaries. While inland water transport has historically proven its ability to deliver freight at scale, its outdated infrastructure poses a significant challenge to its revival. Reorganising the entire British freight industry to favour inland water transport may not be cost-effective.

However, the sector could support the fast-growing last-mile logistics segment, where smaller packages require fewer infrastructure overhauls. Recognising the potential of British rivers as underutilised, congestion-free resources, some freight operators are exploring the opportunities they present. In 2020, DHL Logistics launched a riverboat service in partnership with Thames Clippers Logistics to deliver smaller packages across the River Thames.

Handling up to 30 bags of parcels per trip, the service forms part of DHL’s €1bn (£840m) global investment in decarbonising its network. This initiative adopts a multimodal approach, combining electric cargo bikes with sustainably fuelled inland water transport to create an eco-friendly last-mile delivery solution. At its launch in 2020, Ian Wilson, chief executive of DHL Express UK & Ireland, highlighted the motivation behind the initiative: “With traffic and poor air quality becoming an increasing problem in urban areas such as London, we’re committed to finding a better blend of transport.

This new and unique service, combining electric vehicles, riverboats, and last-mile bikes, creates fast and efficient access across the UK capital.” This small-scale operation is just a drop in the water compared to the full capacity of the Thames and Britain’s inland waterways. Demonstrating that existing piers and docks can support freight remains a task of persuasion. To showcase river freight’s potential, CRP conducted its London Freight River Trial from 27 February to 24 March 2023, providing a proof of concept for using the River Thames for fast, efficient and consistent deliveries.

FAST FACT: In 2023, UK domestic waterway freight volumes hit an all-time low, with only 15.4 million tonnes moved. Source: UK Government Port Freight Annual Statistics 2023

The four-week trial, part of the Defra-funded Clean Air Logistics for London project, involved several freight and delivery partners, including Grid Smarter Cities, Lyreco UK & Ireland, Pedal Me, Port of London Authority (PLA), Speedy Services and Thames Clippers Logistics. Its goals were to improve air quality, deliver low volumes of dry bulk freight, and create a business case for inland waterway transport. The trial demonstrated success, achieving a 92% reduction in NOx emissions with a 12-europallet capacity vessel running on HVO.

The vessel’s average loading time was just 15 minutes, saving an estimated 80 minutes of driving time per journey. The total cost was £51,842, including letting fees. For context, London’s last-mile delivery industry is worth £3.28bn, with global market research firm IMARC predicting a 9.8% annual growth rate. “What’s very interesting is that all the pieces seem to be moving; it’s just a matter of fitting them together like a jigsaw,” reflects Coull. “We’ve proven it can work with the London Light Freight River Trial.” The trial’s success, particularly in attracting external collaboration, was largely due to the financial incentives provided by the CRP. Partners were able to operate with the assurance that any shortfalls would be covered by the trial – a luxury that cannot be relied upon should they establish their own independent operations.

“HVO makes boating more sustainable by replacing fossil diesel with a second-generation biofuel” – Amy-Alys Tillson, campaign officer, Inland Waterway Association

Overcoming the challenges facing inland waterway transport would require significant capital to sustain these fledgling services. What the trial did demonstrate, however, is that targeted investment can deliver tangible results. With adequate funding, inland water transport has the potential to become a viable and sustainable freight option. “There needs to be a point, which I think we’re reaching now, where an operator can use the river, cover their costs, and make it an operationally viable service without depending on external funding,” says Coull.

Opportunity knocks

For inland waterway transport to gain prominence, the industry must adapt to the demands of modern freight. Organisations such as the IWA, CRP and a small number of third-party logistics operators have demonstrated the viability of inland waterway transport as a sustainable freight option. Addressing key challenges such as usage priorities, capacity, and business perception could create a domino effect, driving broader industry change.

“Waterways will continue to play a structurally vital role in climate change adaptation,” concludes Tillson. “[Inland water transport has] the potential to improve the sustainability of freight and remains a key feature of the UK’s industrial heritage.”

The 1998 white paper on the future of freight envisioned an interconnected Britain. It highlighted the potential of inland waterway transport stating: “We want to see the best use made of inland waterways for transporting freight, to keep unnecessary lorries off our roads.” However, the responsibility for realising this vision now lies with the businesses and organisations working to expand river freight.

“There’s a need for policies that support a shift to these sustainable modes, offering incentives to try something different and move towards a more sustainable method,” says Coull. “But I think right now, we’re still far from realising what could be achieved.

Tide over traffic

In a city as dynamic and sprawling as London, river services extend beyond freight to encompass commuter transport, which must constantly evolve to meet the demands of a growing population and shifting priorities. Among the myriad of options, river transport has emerged as an efficient, scenic, and increasingly sustainable alternative to road and rail.Uber Boat by Thames Clippers (UBTC) has positioned itself at the forefront of this transformation, offering a river bus service across the Thames. Connecting 24 piers across London with river bus services running every 10–20 minutes, UBTC’s network links key destinations such as North Greenwich for The O2, Canary Wharf, London Bridge, and Westminster, while also serving residential areas such as Battersea Power Station Pier and Barking Riverside Pier.

Since launching, UBTC has successfully integrated with London’s multimodal transport network, offering commuters and visitors an alternative way to traverse the city while avoiding the congestion of road and rail.

In this Q&A, Geoff Symonds, chief operating officer at UBTC, delves into the service’s operations, its benefits and its role in London’s broader transport ecosystem.

What makes river commuting a compelling alternative to road or rail?

River commuting offers several advantages. Firstly, it alleviates congestion on London’s roads and railways, allowing passengers to sail into central London, avoiding parking fees and congestion charges. Punctuality is another major benefit; boats bypass road traffic and face fewer delays than rail systems. The journey itself is a pleasure – commuters can relax in comfortable seating, enjoy refreshments from our onboard bar, and take in stunning views of London’s riverside landmarks. We also cater to cyclists, with space for up to 14 bikes on our largest vessels, and soon, the Orbit Clipper will accommodate 100 bikes.How are you reducing the environmental impact of your fleet?

Sustainability is at the core of our operations. Over the past two decades, we’ve launched green initiatives, such as hybrid vessels like the Earth, Celestial, and Mars Clippers, which run on battery power in central London and biofuel outside it. This year, we’re launching Orbit Clipper, the UK’s first fully electric zero-emission cross-river ferry, capable of carrying over 20,000 passengers daily.Our goal is to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. To that end, we’re exploring advanced fuel technologies, including hydrogen and methanol, and continually investing in hybrid and electric vessels to replace older models.

What role does river transport play in London’s future?

As cities grow, river transport offers a sustainable, scalable, and innovative solution. By reducing road congestion, cutting emissions, and supporting multimodal integration, river bus services will remain vital to the future of urban mobility in London.

This article was originally published in the February 2025 issue of CiTTi Magazine.

Achievements and innovations in river services will be recognised and celebrated at the fourth annual CiTTi Awards on 25 November 2025 at De Vere Grand Connaught Rooms in London. Visit www.cittiawards.co.uk to learn more about this unmissable event for the UK’s transportation sector!