London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone will be extended this summer to cover the whole of the UK capital to boost air quality. However, questions on the fairness of the road charging scheme remain, as David Smith discovers…

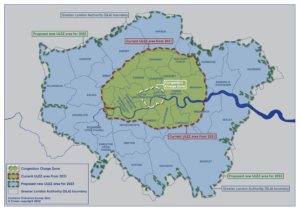

Transport for London (TfL) will expand its Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) across all London boroughs from August 29. The ULEZ requires drivers of older vehicles to pay £12.50 if they drive within the zone, or pay a £160 fine, to be increased to £180. London mayor Sadiq Khan insists the move is essential to protect human health from toxic emissions. TfL points to data showing large improvements in air quality in existing ULEZ zones in Inner London. But there has been strong resistance to the extension, especially from leaders of Outer London’s councils.

“The overriding goal of ULEZ is to reduce toxic emissions. It’s not about cutting traffic like the Congestion Charge. With ULEZ, we want to persuade people to consider driving less polluting vehicles and improve air quality,” says Lucy Hayward-Speight, a principal policy advisor in the TFL transport strategy and planning department.

Hayward-Speight says TfL felt compelled to extend the ULEZ because of the terrible impact on Londoners’ health of toxic levels of pollutants from nitrogen oxides and tiny particles of rubber and metal. About 200,000 non-compliant vehicles are driven regularly in London, she says. “Our 2019 study shows 4,000 deaths a year are attributable to air pollution, and adults have higher rates of dementia, asthma, cancer and lung disease. It’s a myth only Central London has high concentrations of air pollution. Some of the worst areas are in Outer London around busy junctions, high streets and some residential areas and most pollution-related deaths are in Outer London.”

RUC leader

London has a long history of leading the way with road user charging (RUC). TfL launched its first RUC scheme, the Congestion Charge, in 2003. Five years later, the mayor announced London’s first low-emission zone (LEZ), but this only affected heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) over 3.5 tonnes, and buses and coaches weighing more than five tonnes. The true precursor to the ULEZ was the Toxicity Charge, or T-Charge, introduced in 2017. It was the first TfL low-emission scheme to target car owners. Drivers of petrol and diesel cars registered before 2006 had to pay £10 to drive into Central London during weekdays.

Then, in April 2019, the ULEZ replaced the T-Charge in the same Central London zone as the Congestion Charge. The fee rose to £12.50 a day and ULEZ was operational 24/7. Another change from the T-Charge was rules became stricter for diesel drivers. “Diesel has slightly lower carbon emissions than petrol, but for air pollution it is far worse,” says Hayward-Speight. “ULEZ charges apply to diesel cars that don’t meet Euro 6 emission standards or registered before 2015. For petrol cars, it’s Euro 4, which only affects older vehicles registered before 2006.”

Following the introduction of ULEZ in Central London, it was then expanded in October 2021 to cover the entire area between the North and Circular orbital roads, making the zone 18 times as big. Hayward-Speight says the existing ULEZ has had a powerful impact on both driver decisions to switch to cleaner models and air quality, making a strong case for

extension. “For existing ULEZ areas, compliance with the regulations – which means drivers don’t have to pay the fee – is at 94%. When we started ULEZ it was 85%. But from the moment it was talked about, a lot of people started considering switching to newer models,” she says. “We’re expecting a similar impact in Outer London, where compliance is now around 85%.”

The impact of the changes in driver behaviour on air quality has been remarkable, Hayward-Speight says. ULEZ has helped to reduce the quantity of toxic nitrogen dioxide particles by 40% in Central London, as well as cutting CO2 emissions by 6% and particulate matter (PM) by 27%. In the area between the North and Circular orbital roads, where the charge was introduced later, the reduction in nitrogen dioxide is already 20%, she says. “Some improvements can be attributed to people buying newer cars anyway or to lockdowns. But the effect of the lockdowns was fleeting, and we know most of the benefit is down to the ULEZ because other cities have not seen similar reductions.”

Resistance movement

Despite the positive results, the decision to expand has met opposition. In 2022, TfL’s public consultation on widening the zone revealed that 60% of respondents opposed it, rising to 70% in Outer London. Meanwhile, Logistics UK, which represents logistics businesses, has called on TfL to introduce mitigations to allow companies that have ordered replacement vehicles to remain exempt from additional charges while awaiting delivery. “Businesses that rely on second-hand vehicles, such as SMEs, have only limited options for purchasing a Euro-6 vehicle, and delays on delivery of electric vehicles are preventing operators from switching fleets,” says Denise Beedell, senior policy manager at Logistics UK.

The most strident criticism has been from council leaders in Outer London. For example, Hillingdon Council leader, councillor Ian Edwards, expressed his vehement opposition to the “half-baked plans”. “London cannot be treated with a one-size-fits-all approach when the make-up of inner boroughs is incredibly different… Our residents don’t have the luxury of a frequent, multi-layered transport system. Many have little option other than to use their cars for everyday travel. Imposing the ULEZ charge is not only wrongheaded but is completely unfair and will hit the poorest hardest.”

Meanwhile, Harrow Council leader, councillor Paul Osborn, complained that installing hundreds of ANPR cameras in Harrow and thousands across London to administer the scheme would cost hundreds of millions of pounds. And Jason Perry, executive mayor of Croydon, argued it would be a “hammer blow to businesses and residents”, coming on top of an 8.8% rise in council tax.

But Hayward-Speight says TfL has been careful to avoid piling more financial pressure on low-income and disabled people. She says TfL’s impact assessment has provided insights about potential impacts. “It’s worth pointing out low-income Londoners are the least likely to own cars and most likely to live in areas of high pollution. And as it stands, the charge will only affect 15% of car owners. But we recognise we need to help low-income people as it’s harder for them to pay charges,” she says. “The impact assessment suggested we consider a scrappage scheme, which we ended up doing and are doing again.”

The original scrappage scheme made £61m available and the extension to Outer London involves a larger £110m fund. The new scheme opened to Londoners on low-income, or disability benefits, on 30 January 2023. Owners can receive either £2,000, or a lower sum plus one or two TfL annual bus and tram passes. Sole traders, micro-businesses and registered charities will be able to scrap or retrofit vans or minibuses. “It’s a great way of

encouraging people to try buses. With the first scrappage scheme, a third of people didn’t use the money to purchase another vehicle but used it for things such as paying off debts and increased usage of public transport,” she says.

The impact assessment showed further mitigation measures were necessary for disabled people. Whereas those on low-income benefits can receive £2,000, and motorcyclists can get £1,000, disabled people can scrap a wheelchair-accessible vehicle in exchange for £5,000 or receive the same sum to retrofit it. TfL has also introduced grace periods. “One of the biggest changes is bringing in time-limited exemptions for disabled people, so they won’t pay daily charges until 25 October 2027,” she says.

Sign of things to come

The ULEZ was designed by TfL but is run by London-based business processing outsourcer Capita. The original ULEZ area required more than 1,000 signs and nearly 800 cameras to administer. The expansion will demand far higher numbers, but Hayward-Speight believes it is manageable. “We’ve been operating ULEZ in the centre and the North-South Circular area since 2021 and we know how to run it and scale it up. We know how many cameras and what signage we need, and we’ve improved the running of the scrappage scheme. It won’t become too unwieldy,” she says.

TfL’s ground-breaking ULEZ scheme has also received attention from cities around the world. A delegation from Iceland came to London to learn more about ULEZ this January and Hayward-Speight was preparing to speak to Chinese city authorities about the measures. Nevertheless, it is likely London’s ULEZ will eventually be replaced by a simpler scheme. “We have three schemes running, the Congestion Charge, the LEZ for buses and large vans, and the ULEZ. It’s quite complex. None of them depend on how far you drive in a day. We’re looking at different approaches in the long-term, such as distance-based charging, so you’d pay only a small amount to go a short distance, which could be a fairer way of doing it, rather like London bike schemes. But to date there are no proposals,” she says.

The French approach

France has taken a nationwide approach to controlling toxic emissions. The most environmentally damaging vehicles are banned from driving in Low Emission Mobility Zones (ZFE-m) across France and all vehicles entering the zones must display an ecological sticker called Crit’Air, which comes in six different colours.The colours relate to Euro emissions standards and range from green (Category 1) for the cleanest models to dark grey (Category 6) for the dirtiest ones. Cars registered before January 1997 are ineligible and cannot be driven where restrictions apply. In Paris, the Crit’Air sticker is compulsory within the perimeter of the A86 motorway from Monday to Friday from 8am to 8pm.

Several large cities outside the capital have set up ZFE-m zones. To date they are: Lyon, Aix-Marseille, Toulouse, Nice, Montpellier, Strasbourg, Grenoble, Rouen, Reims and Saint-Étienne. But from 2025, all cities and agglomerations with more than 150,000 inhabitants will be required to introduce ZFE-m zones.

This year restrictions are being tightened. Since January 1, all Crit’Air 5 vehicles, or vehicles without a sticker, have been subject to traffic restrictions in ZFE-m zones. In Paris and the Greater Paris area, the traffic ban on Crit’Air 3 cars will apply from July 1 (in addition to existing restrictions on Crit’Air 4, 5). In Lyon, for example, Crit’Air 5 vehicles are now banned and Crit’Air 4, 3 and 2 vehicles will be progressively restricted between 2024 and 2026.

This article was first published in the February 2023 issue of CiTTi Magazine. Read the original article.