With more and more emissions-based road-user charging schemes launching across the UK, Ursula O’Sullivan-Dale speaks to those behind Oxford’s Zero Emission Zone – a pioneering pilot designed to improve air quality, cut carbon emissions and move toward clean travel in the city…

In recent years, road-user charging (RUC) schemes targeted at reducing both emissions and traffic congestion have been cropping up across the UK, from the headline-making London-wide expansion of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) coming this August, to clean air zones (CAZs) appearing in Bath, Birmingham, Bradford, Bristol, Portsmouth, Sheffield and Tyneside, with Greater Manchester having a similar initiative currently under review.

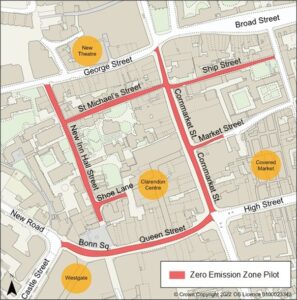

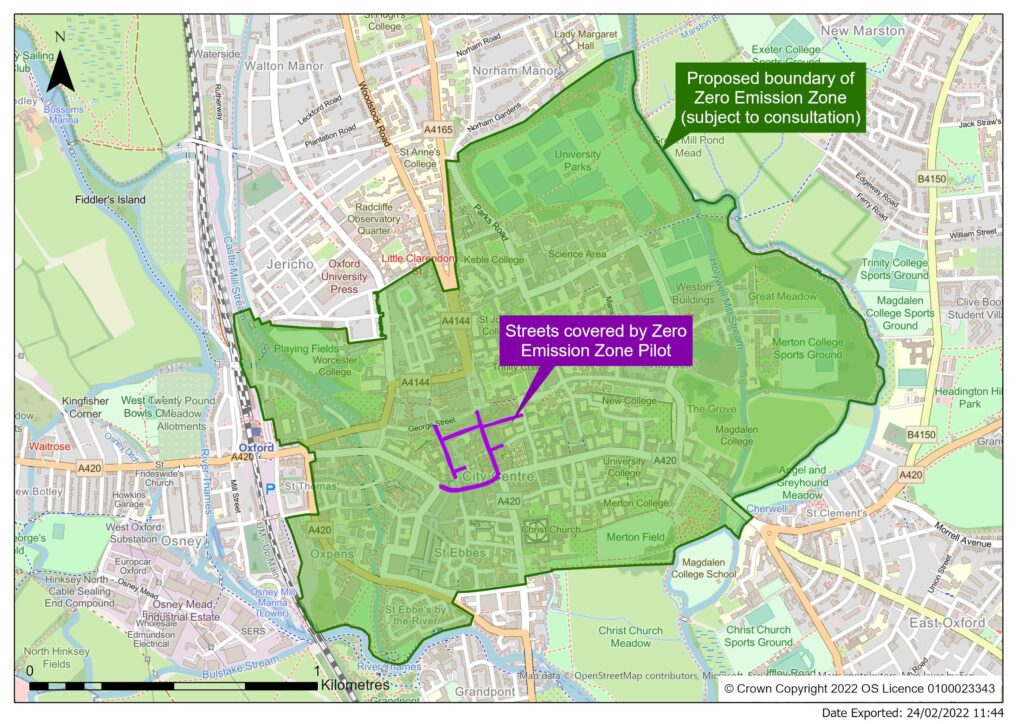

Among this cluster of cities introducing emissions-based RUC schemes is Oxford, which officially launched Britain’s first Zero Emission Zone (ZEZ) pilot on 28 February 2022 to test the waters for a larger ZEZ covering most of Oxford city centre. And unlike the aforementioned ULEZ and CAZs, which focus on low or ultra-low emission vehicles, the new ZEZ guidelines stipulate that zero-emission vehicles alone, such as battery-electric vehicles or hydrogen-powered vehicles can enter the nine-street area from 7am to 7pm free of charge.

With a handful of exceptions, all other non-compliant vehicles face a fee to enter the ZEZ during operating hours, with penalties ranging from £2 to £10 per day, depending on a vehicle’s emission levels. These daily charges are set to increase from a minimum of £4 to a maximum of £20 in August 2025.

Developing the ZEZ

The inception of the ZEZ dates to 2015, when Oxfordshire County Council first outlined the concept as part of its local transport plan. After conducting feasibility studies, the council published updated proposals and launched informal, and then formal, consultations on the project between 2020 and 2021. As with other emission-based RUC schemes implemented across the UK, there are fee exemptions and discounts available for certain businesses and road users.

Interestingly, initial plans to develop a scheme to improve air quality and congestion in Oxford city centre looked very different to today’s ZEZ. On this, councillor Martin Kraftl, principal infrastructure planner at Oxfordshire County Council, says: “The development phase involved a lot of benchmarking… the scheme has evolved a lot since its inception. In 2015, it was intended the ZEZ would ban all but zero-emission vehicles, and then over the years, following various feasibility studies and looking at what was going on elsewhere in the country with clean air zones, it evolved into a road-user charging scheme.

“That was, in large part, due to engagement with local businesses and those affected by the scheme and trying to find a solution that would deliver the outcomes yet strike a balance between access and emissions reduction. A charging scheme felt like a much better way of doing that rather than an outright ban because a charging scheme allows you to be much more sophisticated in how you approach and treat different vehicle types, sizes and emissions categories. All those sorts of things are just not possible with an outright ban.”

Local power

One of the more unique features of the ZEZ, aside from its strict emissions standards, is that the initiative itself originated within Oxford’s local authorities rather the result of a directive from the UK government, as per the various CAZ schemes across England. Instead, the ZEZ has its roots in local transport planning and council professionals from the community.

“This has resulted in a lot of collaborative work between local government professionals, with Oxford City Council leading on commercial engagement as they have, day-to-day, much closer relationships with town-centre businesses”, explains councillor Duncan Enright, cabinet member for travel and development strategy at Oxfordshire County Council, “whereas the county council has fairly regular contact with the UK Department for Transport and therefore led on that.” The county council likewise had the technical competence for the back-end development and heavy lifting related to the various digital resources associated with the project, such as the ZEZ website and online payment system.

On the importance of directing efforts based on local expertise, Louise Upton, cabinet member for health and transport at Oxford City Council, discusses some of the main engagement efforts performed by the city authority: “The early engagement with local businesses was absolutely crucial [to the successful implementation of the scheme]. There were workshops, interviews and a ZEZ partnership for businesses was created so that they could share ideas with which both councils could engage with them on specifically”.

This was, states Upton, especially useful for ensuring approaches to traffic management were targeted, with most of the traffic in ZEZ commercial rather than residential. “For example, there’s an auction house on one of the streets in the zone, and that’s a big problem for them in terms of people bringing very valuable [items] to them. You can’t do it on a cargo bike, so working with the auction house to make sure that businesses are able to survive is absolutely critical, and that includes getting bikes for The Covered Market. We had some government money to do that and were able to help them get cargo bikes for the market specifically.”

Breath of fresh air

Though it is designed to push residents and visitors toward more sustainable forms of transport and redirect and reduce congestion, the ZEZ is, first and foremost, a public health initiative. As Enright explains, the ZEZ has been a “public health intervention, not just a transport intervention” from the start, and that its key ambition is to address “this issue of public health and managing air quality in historic streets where there are very few other options”.

As a result, the ZEZ boundary has been closely defined around the city centre, as this is one of the worst areas for air pollution in the county. Upton concurs: “Particularly, and as far as the city council is concerned, the driving force behind putting the ZEZ in is to improve air quality. A lot of people cycle along the streets within the ZEZ and therefore breathe in lots of poor-quality air. So, it’s not [just] a tool for reducing congestion. It’s not a congestion charge. This is about improving air quality, given that one in 17 deaths in Oxford is linked to poor air quality. That was our driving force.”

As well as focusing on zero-emissions vehicles, there are several other aspects of the ZEZ that make it unique. As Bryan Evans, senior transport planner at Oxfordshire County Council, explains: “There are different levels of emissions that are charged within the scheme. Comparable initiatives such as a clean air zone and London’s ULEZ essentially have one threshold. So, if your vehicle meets that threshold, and if the emissions are cleaner than that threshold, there’s no charge. If it’s the other way, then there is a charge. So, the other schemes have a single threshold, whereas we have several. And so, to determine what the charge would be, we needed to develop a bespoke vehicle emissions checking system, and that was quite a big innovation.”

In this sense, the scheme has proven innovative in its approach to delivering emissions-based RUC. On supporting the technical side of the initiative, Upton continues, “Yes, automatic number plate recognition [ANPR] cameras have been around for a long time, and you can use them to find out the owner of the vehicle and charge them. But our deployment is also linked to letting you know what the emission standards of that vehicle are, so whether you’re going to charge £10 because they’re a diesel or petrol car, £2 if they’re an ultra-low-emission vehicle, or £4 if they’re somewhere in the middle – or nothing if they’re fully electric and zero-emission. So, the ANPR system [we introduced] is quite a special one.”

Despite some differences in its design and implementation, the operation of the Oxford ZEZ is based on many of the same core principles that have influenced the London ULEZ and other CAZ or low-emission zone schemes around the UK. “Some of the exemptions and discounts are modelled quite closely on those other schemes, and, of course, the fundamental principle is the same. That is, you create an incentive to either drive less in the zone or to change vehicles or your behaviour in other ways that produce air quality benefits through a road-user charge. That fundamental principle is the same as with all those other schemes.”

ZE-Z top

With the pilot having been operational for more than 15 months now, the ZEZ appears to be on its way to further expansion in the coming years. According to Evans, a key purpose of the pilot was to test the concept and develop the supporting systems to operate the wider ZEZ to come.

“And I think that it’s been really successful,” says Evans. “We’re satisfied it has demonstrated that the ZEZ concept works with the systems we have in place. With that experience we can be confident about having the necessary systems to expand the scheme to a much wider area in Oxford later.”

In terms of monitoring the ZEZ’s effect on traffic within the pilot area, the two councils have commissioned several surveys and compared those figures with similar ones completed in the same location before the pilot went ahead. However, measuring the full impact of the scheme is not as simple as that, says Evans. “The pilot area has certain characteristics that are helpful for comparison and certain characteristics that make comparison a bit more challenging.”

This is in part because the area is generally characterised by low traffic volumes, pedestrianised streets or streets that are pedestrianised for much of the day. What’s more, most of the nine streets have limited access to vehicles, of which many are exempt from the ZEZ anyway, such as buses and taxis. Furthermore, cycling is disproportionately high in Oxford city centre, with 17.2% of commuters travelling by bike and just 38.2% of Oxford city residents commuting to work by driving a car or van, versus 64.7% across Oxfordshire and 65% in England, according to the UK Office of National Statistics.

This means some comparisons “have a limited value”, Evans continues, “though there is one street in particular that is open to all vehicle types and all traffic types. So that’s good for us to look at, and initial comparison of data suggests a 40% reduction in traffic on that particular street during the operating hours of the scheme, so we’re encouraged by that. That’s quite a substantial reduction in traffic, really.”

Upton also points to some qualitative data that has helped measure the impact of the scheme. “Royal Mail, for example, has moved all of its deliveries to electric vans because of the pilot, and we know that DPD made Oxford its first all-electric delivery vehicle city in 2021. We also have several homegrown companies that are basically cycle couriers, which means the ZEZ has given them a kind of a competitive business advantage in the city.”

Overall, the ZEZ forms a crucial part of the region’s wider ambitions to introduce a cleaner, safer and more active travel-oriented city centre to help reach local climate targets. “This scheme is one part of the county council’s work to move to a zero-emission fleet and to change the way it does things in order to support carbon neutral and carbon positive transport futures.”

Overall, the councillors have been very pleased with public feedback from the scheme, which they attribute to proactive communications and engagement efforts from early on. Upton adds that the ZEZ has been handed between different political representation within the county council, but that it has still received cross-party political support, while also benefiting from effective collaboration between national, county and city authorities.

Enright concludes that he’s been especially surprised at the lack of backlash around the scheme, commenting that, “in political terms, we’ve had some extremely controversial schemes that haven’t even come in and have just been proposed for the future. This one was implemented and has run with substantially less of that kind of pushback on social media or from residents or from national [stakeholders]”.

The positive reception to the ZEZ, though still in its infancy, perhaps reflects a growing acclimatisation to the potential for tailor-made RUC schemes that target emissions and change transport behaviours in non-disruptive ways. Regardless of the broader national implications of the growing prominence of these schemes, the Oxford ZEZ has demonstrated that more ambitious versions of this model are possible through effective and localised transport planning.

Follow the money

One question consistently raised in relation to schemes that charge for the use of roads concerns what happens with the revenue raised. In the case of the Oxford Zero Emission Zone (ZEZ), which, being an RUC scheme, in accordance with the Transport Act 2000, restricts the use of profits or income from the scheme to certain applications. As Oxfordshire County Council’s Martin Kraftl explains, “the funding is used to cover the costs of operating the scheme. Anything left over must be used for schemes that facilitate local transport policies”.The implementation of a system to manage this payment isn’t necessarily in the final form that could come with the expanded ZEZ. Commenting on the feedback received from local businesses on the payment system, Kraftl says this had been largely defined by calls for an accounts-based system, rather than the individual payment process, which the ZEZ website currently facilitates.

Working out these kinks will form a key part of the successful expansion of the scheme in the coming years, with councillors unsure of an exact date but optimistic at the prospect of an expansion.

This article was first published in the June issue of CiTTi Magazine. Read the original article.