With growing opposition to the reallocation of road space for increased numbers of cyclists and pedestrians, are active travel zones good for cities? Katie Searles reports…

A London Council report published in October 2020 attributed poor air quality to the premature deaths of 9,400 people in the UK capital each year, at a cost of up to £3.7bn to the National Health Service. With the same report citing road transport as the main contributor to air pollution, it is no surprise that major cities such as London are striving to get people out of cars and into more sustainable modes of transport.

Encouraging a modal shift from motorised vehicles to cycling and walking has been at the forefront of local authority policy for years, mainly to help counteract a number of rising health concerns, such as obesity and lung and heart disease, among the general population. This focus on active travel accelerated massively last April and May when the UK and devolved governments made emergency funds available to help councils meet unprecedented levels of walking and cycling witnessed across the country as people sought alternatives to public transport during the early part of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In England, £250m was released immediately, while in Scotland, some £38.97m was allocated to local authorities through the Spaces for People initiative by August 2020. Within weeks of both funds being made available, pop-up walking and cycling infrastructure, temporary junctions and cycle- and bus-only corridors were fast-tracked into existence, changing the face of towns and cities throughout the UK as local authorities scrambled to apply for a portion of the government funding.

London’s Streetspace scheme, unveiled by mayor of London Sadiq Khan and Transport for London (TfL) in May 2020, was one such programme to successfully apply for funding. Planning to rapidly expand the amount of physical infrastructure dedicated to walking and cycling in the UK capital, Streetspace, according to its makers, aimed to relieve pressure on other transport modes by reducing crowding on tube and train lines and bus corridors, as well as help enable social distancing upon subsequent easing of Covid-19 lockdown restrictions.

Modelling by TfL at the time revealed that there could be more than a 10-fold increase in kilometres cycled and up to five times the amount of walking, compared to pre-Covid levels, in London if demand returned. Thus, Streetspace saw more than 50km of new or upgraded cycling infrastructure planned, along with more than 16,500m2 of extra pavement space on the TfL network and installation of some 1,540 extra cycle parking spaces on high streets and at transport hubs across London.

While Streetspace promised to be a transport panacea during unprecedented times, the pace of implementation led to some undesired results. In January 2021, the scheme was ruled unlawful by the High Court after the United Trade Action Group and the Licensed Taxi Drivers Association successfully argued that it disadvantaged taxi drivers. As a result, the court ordered that the Streetspace Plan, Interim Guidance to Boroughs and A10 Bishopgate Traffic Order be halted.

In the ruling Justice Lang said that TfL “took advantage of the pandemic” to push through “radical changes” to London’s streets. In the High Court’s view, the “ill-considered” response to the pandemic saw taxis banned from using bus lanes in order to ply for trade. According to Lang, the “the needs of people with protected characteristics, including the elderly or disabled”, were “not considered” when the plans were put in place.

The High Court’s ruling was welcomed by pan-impairment organisation Transport for All, whose CEO, Kirsty Hoyle, said via an official statement: “Many local authorities and transport bodies failed to carry out meaningful consultations with disabled people. In our research, three in four participants expressed frustration at the way Streetspace changes have been communicated, citing a lack of engagement, consultation and accessible information from authorities.”

Hoyle has since called for change and stressed that any active travel scheme plan needs to be “of high quality [and] co-produced with disabled people directly impacted by these initiatives”.

TfL is currently seeking clarification on a number of legal issues around Streetspace and recently won the right to ask the Court of Appeal – the highest court within England and Wales – to overturn the ruling.

Helen Cansick, head of healthy streets delivery at TfL, says: “While we were disappointed by the ruling, we understand that such schemes always have winners and losers and that any shared mobility plan requires balances.”

Additionally, Natalie Chapman, head of urban policy at freight trade association Logistics UK, believes there are lessons to be learnt from the ruling. “It’s clear that all these [temporary active travel] schemes were pushed through very quickly due to government funding deadlines, which has subsequently impacted on how Streetspace was designed and implemented, as well as the ruling itself,” she says. “Skipping the key engagement stage meant the scheme missed a lot of competing priorities.”

Mixed modes

But as cities begin to open up once again following implementation of the UK government’s four-stage easing of lockdown restrictions, an opportunity to monitor the varying ways in which road space is used has presented itself.

According to Cansick, it is only through data and feedback that local authorities and transport bodies can then make informed decisions. Furthermore, she believes it is the data itself that will highlight the long-term value of active travel schemes and prove the benefits of sustainable transport modes for both city residents and businesses.

“We’re very keen that people use public transport when they come back into the city,” she says. “TfL has a really strong role to play in creating the economic and cultural vibrancy of London and cycling and walking have always been part of that. What the pandemic has shown us is that more people are willing to try an active travel mode. We need to focus on giving them the facilities to do that, and to do it safely.”

To achieve this, Cansick explains that it is not always about providing specific infrastructure, but rather creating harmony between a mix of urban transport options. For example, building an ecosystem where cyclists feel safe to travel on roads without protected or segregated sections.

Chapman agrees but has reservations about how such an ecosystem would work in the real world. “We need to be clear about who has rights to what infrastructure, and at what time of day, because if you make everything a shared space you can then create other conflicts. We want everyone to share the road safely together.”

According to Chapman, active travel schemes can’t afford to be too narrow in their focus and warns that, whenever local authorities and transport bodies encourage more people to walk and cycle, more consideration of a broader range of road users is needed.

In that vein, Rich Nickson, active travel director for Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM), sees walking and cycling as a complementary mode alongside Manchester’s tram and bus network. “Walking and cycling is the first and last step of every journey, potentially,” he explains. “Our challenge now is to work together in a truly integrated way to support public transport recovery. But we also recognise that active travel can play a really positive part in the economic, social and health revolution; the first and last mile.”

According to Nickson, TfGM regards Manchester’s £19m of active travel funding from the government as an opportunity to experiment but does not want current measures to be viewed as “disposable”.

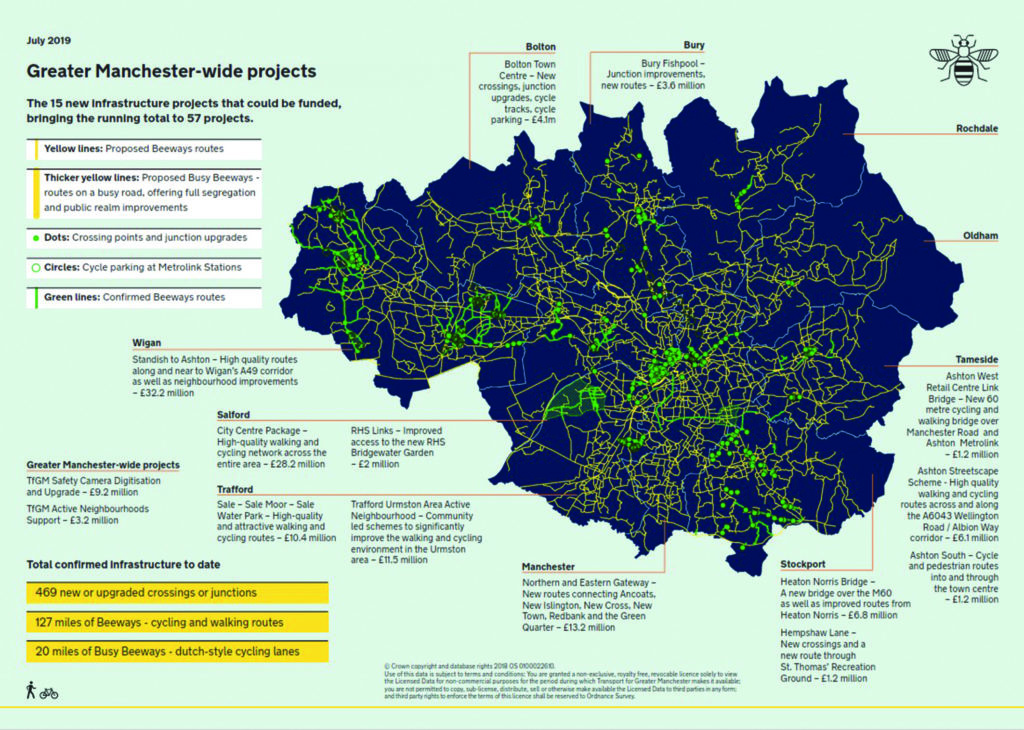

Instead, TfGM regards the temporary infrastructure currently in place as a mechanism for further testing and trialling of what could become permanent schemes in the future. This includes the city’s 10-year Bee Network plan, a £1.5bn protected cycling and walking route covering all of Greater Manchester’s 10 districts. When completed, the route will be the UK’s largest cycling and walking network covering 1,800 miles and 2,400 new crossings. Around 55 miles of routes will be completed by Christmas 2021 plus around 17 so-called active neighbourhoods.

As Nickson explains, active travel schemes are not just key to cities’ recovery from Covid-19, they will also shape the way people, businesses, goods and materials travel through them in the future. “Walking and cycling have roles to play in whatever our new future might look like, especially around decarbonising transport or generating a more equitable society, where those without access to cars, or those who choose not to use any form of mechanised transport, are on a level playing field.”

It’s good to talk

Nickson believes open and honest conversations are vital when developing active travel schemes, whether they are temporary initiatives or more permanent programmes. “These dialogues should include activists, politicians, residents, community leaders, faith leaders and people involved in charitable activities,” he says. “Together these organisations can discuss the culture required, and the change needed to support people being more active, more often.”

According to Nickson, only through consultation and engagement can local authorities develop a best practice for implementing active travel schemes and prevent possible pitfalls similar to those experienced by TfL with Streetspace.

This is echoed by Cansick, who reiterates that any dialogue must be data-led. “We need to listen to people, listen to communities we are impacting and benefitting, and we need to listen to businesses. Only then can we really get people to experience [active travel schemes] and decide whether they like them or not. And using data to do that is what’s needed going forward.”

Engagement with safety campaigners should also be at the forefront of such discussions, says Chapman, who believes that all parties should want to protect all road users in shared spaces, regardless of their chosen transport mode. She adds that training and education programmes aren’t enough on their own and believes the infrastructure itself must be used to protect road users. “The infrastructure and how it is designed is so important,” she says.

“For years and years, we’ve seen cycle lanes marked up on the inside of vehicles, encouraging cyclists to go up the near side of HGVs, which is the most dangerous place cyclists can place themselves, particularly if that vehicle is about to turn left.

“But infrastructure can’t make people feel safer unless there’s clarity about the rights of road users. There’s been a lack of clarity with some of these temporary schemes, and people aren’t sure who’s has right of way. This lack of clarity could lead to road rage or frustration and have a severe impact on safety. It’s really important that these schemes are constantly reviewed, so that we’re clear on what the outcomes should be.”

Inclusion illusion?

In addition to providing proper infrastructure and guidance over road usage, local authorities and transport bodies understand that there is also work to be done to encourage people to walk or cycle, no matter their income, age or background. Nickson explains: “We recognise that, traditionally, certain communities don’t tend to engage. There are social and health inequalities that you can plot on a map, which relate to certain demographics and certain physical areas of a city or urban region.

“We’re trying to reach out to those communities because there is a risk, of course, that cycling is seen as a very white, middle-class, male-dominated activity. We want to try to overcome that by reaching out to women, black, Asian minority, ethnic communities who don’t ordinarily cycle. It’s understanding how we can reach into those communities and create community champions.”

TfGM benefits from grants from the London Marathon Charitable Trust (LMCT) to help it challenge inequalities of access. The LMCT aims to encourage and support all members of local communities to become and remain physically active. Its grants can be used for bike loans, bike maintenance and cycling clubs, through to particular sorts of cycling training for people with health needs.

As Cansick concludes, active travel “is just not just for a certain type of individual. It’s for everybody”.

Building better

Could cities learn a thing or two from more rural areas about how to plan, design and implement active travel zones that work for everyone? Perhaps. As part of plans to build a new garden town in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire Council has commissioned an 18km (11.1-mile) orbital park route that will connect with existing walking and cycling routes, providing a green corridor to the surrounding villages and local countryside.It is one of many newbuild developments that forecast a shift to green transportation and, within the earliest planning stages, put a real focus on active travel.

Aylesbury’s Gardenway is being designed to be fully accessible and provide dedicated routes for walking, wheeling and cycling.

According to councillor Steve Bowles, cabinet member for town centre regeneration, Buckinghamshire Council, the Gardenway will be more than a cycle path, connecting other transport modes including e-scooters, e-bikes and provide an opportunity for cargo bike deliveries.

“The Gardenway will build on a cultural shift, which may have started during the pandemic, but will continue long after, as not only local government focuses on active travel schemes, but also local people stick to a new healthier lifestyle,” he says.

Key to the success of the Gardenway project thus far has been how those involved in its development have involved the public. Amy Priestley, urban designer at transport and public space design practice, Urban Movement, which led co-design workshops with members of the local community, says: “We’ve been a victim of its own success, and people want more. So, we’re developing more of a network of routes and complimentary routes. It’s been overwhelmingly positive, and people are really keen to see it.”

Likewise, Ulrika Diallo, project lead, Aylesbury Garden Town programme at Buckinghamshire Council, attributes the project’s success to “early front-loading engagement, which has provided invaluable feedback”. Diallo says this was especially important when representing disability groups.

“The key message that came through was to design the scheme in such a way that there is not an area specifically for wheelchair users but to design the whole thing so that a wheelchair users can use it all. We’ve made a massive effort to really reach as far and as wide as we could, and really to touch as many communities as possible.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of CiTTi Magazine