David Smith finds out how smart card payments are transforming public transport ticketing…

Transport for London (TfL) took the game-changing decision to introduce contactless payments back in 2014. But, even as late as 2016, a lot of passengers arriving at Euston Station would join the crowds queuing to buy Oyster cards, or top up the ones they owned. “We had staff going up to them in the queue and saying ‘have you got a contactless card?’ ‘Yes’. ‘Well, you can just leave the queue and travel. It costs the same.’ They couldn’t believe it. It seemed too good to be true,” says Mike Tuckett, TfL’s head of customer payments.

TfL’s earlier launch of Oyster cards in 2004 was not a world-first as Hong Kong had introduced smartcard payments in 2003. But London was the first city to bring in contactless payments and it had an immediate influence around the world. Major cities such as New York and Sydney rushed to emulate London and TfL’s proprietary software netted it £15m. “Our central philosophy is to abolish the whole notion of a ticket. No one wants, or needs them, anymore. And we’ve proved that when you remove barriers, you increase ridership and lower the cost of your operations,” says Tuckett.

The biggest commercial impact, he says, came from the initial introduction of Oyster smartcards. This became clear in 2010 when TfL added Oyster pay to about 200 train-operating stations in London, but several train companies were slow to sign up. Stations that added pay-as-you-go (PAYG) saw a 4% upturn in revenue compared to the stations stuck with old-fashioned ticketing. The effect of the jump to contactless, Tuckett admits, is harder to measure, but TfL analysis estimates an increase of 1% ridership. Despite the rise, Oyster cards will be retained to make payments as inclusive as possible. “Some passengers are unbanked, and others prefer to charge their cards at the start of the week as a way of managing money. We envisage keeping Oyster indefinitely as a parallel sister product to contactless,” he says.

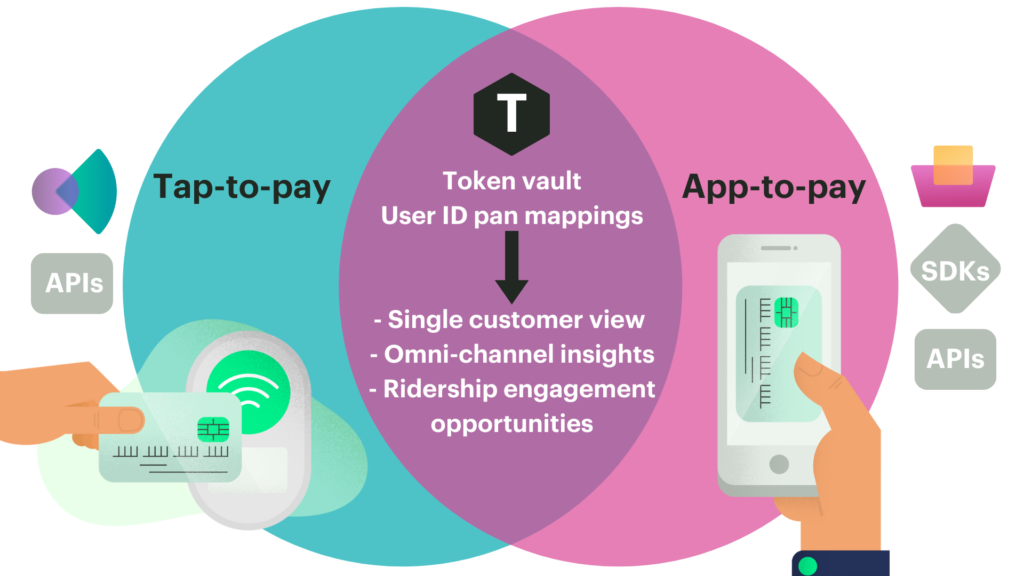

In recent years, Tuckett has observed two major payments trends in London. First, contactless payments have gradually become dominant, with 72% of transactions.

Within this broader contactless trend, there is a growing move towards mobile payments. In 2019, TfL launched its Express Transit feature, allowing Apple Pay users to designate specific cards for travel payments so they don’t need biometric ID when tapping in and out. The second and more interesting trend, he says, is that passengers are purchasing PAYG tickets instead of season tickets. PAYG accounts for 75% of journeys on the underground today. “Even before the pandemic this was happening, but Covid-19 accelerated it as fewer people wanted to be in London all week and it became pointless to invest in unlimited rides,” he says. “In any case, TfL’s capping system works out the cheapest ticket on PAYG so you never pay more than for a weekly, or daily, pass. This feature takes away awkward decision-making and is also equitable. For an annual ticket, there can be a slight advantage, but it’s unusual.”

One of many British transport operators influenced by TfL’s innovative thinking is the large East Midlands bus operator Trentbarton, which offers a multitude of journeys around the cities of Nottingham, Derby, Leicester and their surrounding shires. Emulating TfL’s Oyster pay, Trentbarton introduced Mango cards in 2008. Over the next 12 years the company issued 678,000 of the smartcards and last year there were 100,000 still in use. Just like Oyster cards, passengers had to scan Mango cards when they got on and off the buses.

Targeted ticketing

Trentbarton continued on a similar trajectory to TfL when it introduced contactless payments in November 2019. Until August 2020, the company required two types of ticket machines on buses to allow both contactless and Mango card payments. But last summer Trentbarton launched their Mango app, which replaced smartcards with online payments. Developed with technology provider ACT, a Fujitsu-owned company, Trentbarton explains it is the first account-based ticketing app from a bus company.

“We wanted to develop account-based ticketing because of the benefits of having a lot more calculation happening in the background of a system,” says Mark Greasley, group projects director, Trentbarton. “It allows us to have more targeted offers and types of accounts than before. Passengers can still use their bank cards to pay on the Ticketer machines near the driver, but it’s better to download the app as there are more discounts available. We also have a capping fare structure so passengers never pay more than the best value for a day, week or 28-day period, which takes away the hassle. All the calculations are done automatically overnight.”

Payment technology providers have also altered their strategies in recent years. Cities used to pay hundreds of millions of pounds for bespoke payment systems. But Amin Shayan, CEO of Littlepay, an Australian transit payment service provider, says agencies have far more choice now. Littlepay’s strategy, he says, is to provide an integration hub and leave the transport agencies free to select all the other suppliers. The model is proving popular with private bus companies in the UK, where Littlepay has 70% of the market outside London.

“Agencies find the old bespoke model unattractive and they’re waking up to the fact that no one has to have end-to-end solutions. We just provide APIs and documentation so they aren’t locked into a built system. Agencies used to buy all-in-one systems and now they can choose separate, modular components. If one element isn’t working or there’s a better offer, they can swap it out. Our main competitors are companies that used to build bespoke solutions but are now offering off-the-shelf integrated products that they first developed for other cities.”

Littlepay’s largest current project is to provide open-loop payments on public transport for Finland’s capital Helsinki and the second largest city, Tampere. Littlepay won the contract with Helsinki Regional Transport (HSL) last year to enable contactless EMV payments and the system is up and running on selected ferries, trams and buses. “In Helsinki, our technology sits between the banking systems and the hardware vendors who are selected from multiple bidders. We also offer services like fare calculation, aggregation and capping. But some agencies, such as Helsinki, have developed their own calculation software,” he says.

A similarly agnostic approach is being taken by Unicard, a British provider of software payment solutions that works with 63 local authorities in the UK. Earlier this year, Transport Scotland selected Unicard’s Host Operator, or Processing System (HOPS), to manage its bus travel scheme, including free travel for all under 22s. It is Unicard’s biggest project to date with around three million passengers using the network. HOPS enables account-based ticketing, which works out the best possible fares for all rides. Aside from cash, passengers choose between three payment methods: Smartcards, which are primarily run off the ITSO British standard, barcode ticketing, or contactless EMV bank cards linked to an account with credit.

“The system is tech agnostic and even if Dundee and Edinburgh are running different systems, we can provide a shared backbone that links them together,” says Alex Sbardella, Unicard’s head of product.

“We are keen to push an interoperability agenda. As we work with so many local authorities, we could theoretically provide tickets for travel all the way from Southampton to Edinburgh.”

Shared solution

Technically, Unicard could create a system for shared payments across 63 operators in a matter of weeks, he says. A much greater challenging is persuading rival operators to agree revenue splits. “The UK’s private operators are not keen on giving up relationships with customers, or money. Rail has worked out a way to share revenues between providers so it’s possible although it’s hugely complicated. Probably the only way is for the UK Department for Transport (DfT) to hold everyone’s feet to the fire, and at a lower level, for the regional and local transport bodies to make it integral to their marketing contracts. Ultimately, we have to talk about standardisation and ‘coopetition’, a horrible word, but an important concept as it’s about working together for mutual gain.”

Unicard is developing payment solutions for Solent Transport’s Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) project, which will provide a unified digital transport service across multiple modes by 2024. The scheme integrates rail, ferry, bus and scooter provision, as well as demand-responsive transport and smart parking. The UK government has contributed £2.4m in funding from the DfT. “The investment is essential. No one to date has made a MaaS scheme work without the help of excessive public money,” says Sbardella.

Trentbarton’s Greasley has a similar vision of future payments. He would like to see the Mango app become multi-tenanted. Other operators, such as Stagecoach and Aviva, would share the proceeds with Trentbarton. Greasley says rival operators are already in discussions to develop a specification for multi-operator systems. “We cannot have the tail wagging the dog. Our systems have to support the best offer for the customers. I don’t see why it couldn’t happen, and we could even involve rail or scooter operators in a MaaS system,” he says.

Clean air credit

This summer, Birmingham City Council launched its £10m Clean Air Zone Vehicle Scrappage and Travel Credit Scheme. People working in the city’s clean air zone (CAZ), earning less than £30,000 a year, can scrap a vehicle that would otherwise be subject to a daily fee of £8 to enter the zone. In return the drivers receive a £2,000 grant to use on a ‘travel credit’ for the Transport for West Midlands’ Swift Card, which is used to pay for trains, buses and the Metro. If they prefer, they can spend the money on a new vehicle that meets the CAZ’s emission standards.Birmingham’s CAZ went live on 01 June 2021 and charged owners of the most polluting vehicles to drive within the A4540 Middleway (but not the Middleway itself). “It’s a great way of getting the clunkers off the road and encouraging drivers to use public transport,” says Unicard’s Alex Sbardella. “However, the problem with a lot of marketing is it is targeting people who use buses every day. It might help a bit to persuade them to take a scooter instead for part of the journey. But what we really want is to target people that drive to work and give them an incentive to travel more sustainably.”

This article was originally published in the September 2021 issue of CiTTi magazine.